![]() Faster

Access Within

China, Click

for Main Menu amoymagic.mts.cn

Faster

Access Within

China, Click

for Main Menu amoymagic.mts.cn

Travel Links![]()

![]() AmoyMagic

(Guide)

AmoyMagic

(Guide)

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Quanzhou

(Zayton!)

Quanzhou

(Zayton!)

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Wuyi

Mtn.

Wuyi

Mtn.

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Fujian

Foto Album!

Fujian

Foto Album!

![]() MagicFujian

(Guide)

MagicFujian

(Guide)

![]() Travel

Info, Guides

Travel

Info, Guides

![]() Discover

Gulangyu

Discover

Gulangyu

![]() Fujian

Adventure

Fujian

Adventure

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Fujian

Bridges

Fujian

Bridges

![]() Order

Books Online

Order

Books Online

![]() Letters

from Readers

Letters

from Readers

![]() A.M.ForumJoin

us!

A.M.ForumJoin

us!![]()

Outside China?

Click Here for Faster Access!

Inside China?

Click Here for faster Access!

Back to Top

AmoyMagic--Guide

to Xiamen & Fujian

Copyright 2006 by Sue Brown & Dr.

Bill, Xiamen Univ.

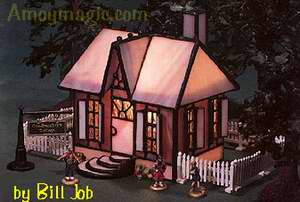

Since Bill & Kitty Job arrived in Xiamen in 1987, their vision and innovative techniques have virtually transformed the global glass industry, and at the same time they've brought about changes to Fujian as well by providing employment opportunities to villagers in impoverished mountain regions.

The Meixia company, Xiamen’s first solely foreign-owned enterprise, grew from a modest investment of $10,000 in 1988 to an estimated worth of over $2 million by 2000. A 1992 Wall Street Journal recognized Bill Job as a “pioneer business spirit and innovative artist,” and a leader in the stained glass industry.

Bill

Job's unique woven "Job Glass®", made from scrap that he

once paid to have carted off and buried, is one of the most innovative

types of glass to be produced in centuries, and some of Job’s production

techniques are far ahead of any other firm.

Bill

Job's unique woven "Job Glass®", made from scrap that he

once paid to have carted off and buried, is one of the most innovative

types of glass to be produced in centuries, and some of Job’s production

techniques are far ahead of any other firm.

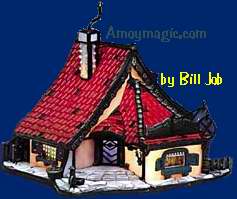

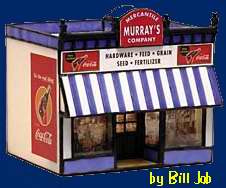

During the 1990s, Job’s innovations helped spawn an entire new industry of stained glass handicrafts. Thousands of avid Bill Job enthusiasts and collectors anxiously awaited each new edition of Job’s glass lighthouses, miniature cottages, or Disney theme products. But Bill Job learned that too great a demand could be almost as worrisome as too small a demand. When demand outstripped supply, competitors sprang up out of the woodworks to meet that demand. To his chagrin, Job not only created both the industry and his competition, but in some cases also trained them to compete against him!

Meixia Handicraft Company

Bill Job was born in Tennessee in 1948, and after two years of college spent 4 years in the Navy. In 1972, just before leaving the Navy, he spent several days in Hong Kong, which wet his appetite for the Orient and China. “Job recounts,

“I was overwhelmed by our Western arrogance of

such a great country. I felt the Chinese are so willing to learn about

us, but we Americans aren’t as ready to learn about China. It wasn’t

right, and I decided to do something in China myself.”

But it was 15 years before he made it to China.

In 1974, he married Kitty and got a degree in Philosophy, followed by

a Master’s Degree. After his father died, he and his brothers started

a carpentry business in which they produced high quality solid wood furniture

and beds.

The first thing Bill Job told Kitty when he met her was that he planned

to move to China to learn about the language and culture, and do something

towards helping the country’s development. In 1986 he heard of Xiamen,

and visited the island for a week in October to scope out the land.

On September 2, 1987, Bill, Kitty and their girls Patty and Christy moved

to Xiamen, where they settled on Gulangyu Island and put the girls in

a local school.

Mexia was born in March 1988 when Bill got a license

to produce fish flies, wood products, and glass products. He chose such

an unorthodox combination of products because he had an immediate market

for fish flies, and glass was a labor-intensive field that he suspected

would eventually have a good market. But Bill did not even qualify as

an amateur glassmaker. Asked what he knew about glass making, he responded,

“Not a thing. I took a short course and read books.”

When Bill Job’s partner died of Lou Gehrig’s Disease, he decided

to change his plans and focus on the glass business. Bill began with beveled-glass

because it was labor intensive and needed no imported equipment or materials.

The expert that Bill had brought in from the states to advise him was surprised to have a nicely dressed young girl show up on his doorstep one day and ask him to have lunch with a Chinese businessman. It turned out he was trying to lure the expert away from Meixia; it wasn’t the last time that Job had to cope with competitors, from both China and America, stealing not only expertise but actual designs.

Sandblasting and Tiffany

When the beveled glass business failed, Bill Job turned to sand blasting. He knew nothing about sand blasting, but he read some books on it, constructed his own blasting equipment, and began turning out designs. He trained people left and right, only to have them leave his own employee and begin their own sandblasting businesses. Some of them actually made bids using Meixia’s name, and put the Meixia name on their company doors. Job recalls, “I would have done better off training people to go into business, and charging them Y 10,000 each for the training!”

Meixia survived for several months on sandblasting, but an order from the Fuzhou Telecommunications Office was Meixia’s ticket into the glass industry. They commissioned Bill Job to produce two large glass murals. He in turn hired a Chinese artist from Gulangyu to design it. He earned enough from this job to import extra stained glass, which he used to produce museum quality reproductions of Tiffany lampshades.

Shortly afterwards, a medical doctor from the states passed through Xiamen, ordered an entire container load of quality glass lamp shades, and gave Meixia one year to make them. This one year grace period also gave Job the opportunity to perfect the glass skills needed.

Finding

Meixia’s Niche

Finding

Meixia’s Niche

While learning the ropes of glassmaking, Meixia was ‘discovered’

by a Taiwanese businessman who needed a factory to produce glass lamps.

The two firms formed a relationship that lasted two years. Meixia grew

from 25 to 125 people, but in late 1992, the Taiwanese man opened his

own factory. This forced Job to reevaluate Meixia’s strengths and

weaknesses, and in doing so he found his niche.

Bill Job recounts,”

“We had many weaknesses. We didn’t know our customers personally,

didn’t know the market, and had little financial backing. We just

could not compete with the Taiwanese head on. Here is where Peter Drucker’s

‘Innovation & Entrepreneurship helped.”

Drucker’s book taught Job to reevaluate his strengths

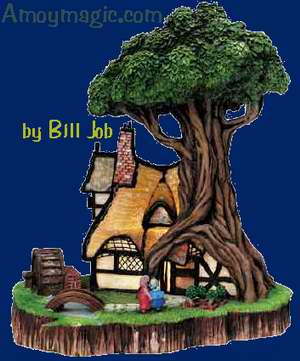

and to try to do something new that the market could respond to. Bill

Job said, “Drucker also stressed being the best in the world at

something. I thought about it, and reasoned that many people in the states

were collecting ceramic or porcelain miniature houses with tiny lights

within—but you could only see the lights from the small windows

or doors. If I made similar houses from glass, the entire house would

glow.”

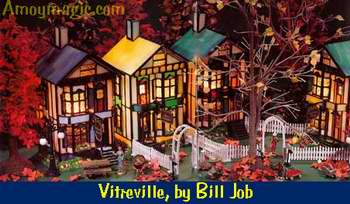

This idea, which emerged in the form of Vitreville™ collectibles,

was to create an entirely new product and market.

Vitreville™

In January 1993, armed with samples of his new product, Job attended the L.A. Gift Show, where he met a man looking for a product to market. After several others had evaluated the concept, the two men shook hands and went to work—only to find they could not keep up with demand.

During the gift show, David, the marketer, lost five

pounds during the 3 days that he wrote orders nonstop. Within one month,

they had enough orders to keep the firm busy for an entire year. Job said,

“Too big a demand was bad. It caused potential customers to find

others to make and develop my product. Within six months, twelve competitors

were confusing and destabilizing the market with poor quality copies.”

Niche

Within a Niche

Niche

Within a Niche

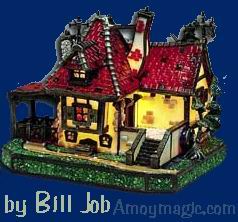

To survive, Job now had to find something to set his product apart, to add a distinctive competence that would give him a niche within his newly created niche. He hit upon the idea of using pewter castings and glass fusing capability to add details that the competition claimed were impossible to accomplish.

After seven years in that market, Job was recognized by many as the best in the world, but he was plagued throughout the years by marketing companies that grew, became unstable, and failed because of their own short-sighted policies. Job said, “They over extended us, and treated people badly..."

Job has also had trouble maintaining the integrity of

the collectible market. Job’s collectible products increase in value

because he limits their production and refuses to discount them. Unfortunately,

one newly designed piece on his office desk was stolen by a visitor, who

returned to America, set up a factory, and sold the mass-produced discounted

copies to a mammoth American retailer, which in turn sold them across

America at bargain-basement prices.

The lawsuit lasted two years. Job won, but never did recoup the $140,000

he spent protecting his market. But Job says it was worth it. “I

sent out a strong message.”

Innovation & Job Glass®

In spite of the ‘strong message,’ subsequent years witnessed a decline in the collectibles market, but Job continued to innovate, creating not only new products but new materials and production processes as well. Job said, “I have a principle: always think of why things are done one way, when a better way could be thought of.”

Taiwanese lamp makers their lampshades in 3 parts, but the joints were large, and the lamps were not round. Bill suggested making the lamp around a mould, but was told, “That’s foolish. You would not be able to get the lamp off the mould.”

“Use a mould that can break down,” Job countered (probably unaware that the Egyptians had used a similar technique thousands of years ago). Within three hours Job had developed a cheap, simple plaster mould, and a technique that is now used in almost every glass lamp factory in Asia.

Another problem that vexed Job was scrap glass. He used to pay a firm to haul it off by the truckload and bury it. The glass experts all affirmed that the multi-colored scraps of glass were useless, but Job continued to experiment on ways to avoid the waste; he was also concerned about the environmental issues. He finally hit upon Job Glass®, one of the most novel glass materials to hit the industry in decades. The idea was such a hit that Job quickly ran out of scrap glass and had to buy the ‘useless’ waste from other companies.

Job

Glass®, which resembles plaid or plain fabric, is made by weaving

together strips of ‘spaghetti’ glass and fusing them at high

temperature. It sounds simple enough, but the technological obstacles

to overcome were formidable for a man who, when he began in the glass

industry, wasn’t even at hobbyist level. Job turned once again to

books. He experimented with various techniques, and different temperatures.

Ever inventive, he solved the problem of how to produce uniform flat ribbons

of glass by using a Chinese noodle maker that he bought on the street

for about $35.

Job

Glass®, which resembles plaid or plain fabric, is made by weaving

together strips of ‘spaghetti’ glass and fusing them at high

temperature. It sounds simple enough, but the technological obstacles

to overcome were formidable for a man who, when he began in the glass

industry, wasn’t even at hobbyist level. Job turned once again to

books. He experimented with various techniques, and different temperatures.

Ever inventive, he solved the problem of how to produce uniform flat ribbons

of glass by using a Chinese noodle maker that he bought on the street

for about $35.

Job used his newly created accent glass to produce lampshades, and after visiting several lampshade manufacturers, he had enough orders to offset the decline in collectible houses. While Job enjoyed the artistic accomplishment from designing the collectibles, they were too labor intensive, had lower profits, and a smaller market than products like lampshades.

Job Glass® turned out to have other uses as well.

Meixia produces woven glass bowls, and unique candleholders produced by

simply allowing a square of Job Glass to melt over a support. Job Glass®

photo frames have also become popular, and are sold with other choice

products over the Internet (the frames, of course, sport photos of the

Jobs’ two daughters).

Job Glass® Products

Innovations like the plaster mould technique, and using a $35 noodle maker to produce Job Glass®, are simple but they work. Job said, “Always go with simplicity if it achieves the desired results….Of course, simplicity is a waste of time if it doesn’t work.”

Job added,

“When possible, it is always good to have our unique products or

technologies to set us apart, because otherwise what we do can be copied

by any of the hundreds of Chinese firms now using stained glass.

“We have focused on bring technology into the company that few others

would consider. We now produce samples entirely on the computer, and e-mail

them around the world for approval without cutting a single piece of glass.”

Once Meixia’s

computerized designs are approved by the buyer, the glass itself can be

cut out using a hi-tech computerized water jet glass cutter that can cut

through one inch iron as if it were soft butter. The computerized cutter

can produce intricate designs that were unthinkable by hand. Job notes,

“We are not using machines to replace handwork, but to give us capabilities

that were impossible before.”

Once Meixia’s

computerized designs are approved by the buyer, the glass itself can be

cut out using a hi-tech computerized water jet glass cutter that can cut

through one inch iron as if it were soft butter. The computerized cutter

can produce intricate designs that were unthinkable by hand. Job notes,

“We are not using machines to replace handwork, but to give us capabilities

that were impossible before.”

Meixia’s unique capabilities has helped the firm land accounts with companies like Coca-Cola and Disney. Disney mailed him a photo of a Disney collectible house that they wanted produced in glass, and asked for a sample. Unfortunately, it was technically impossible to produce the product to their specifications. Bill tackled the project anyway, for as he said, “I am always thinking about solving problems.”

One problem was how to shape flat stained glass into curves,

and heat it to blend or fuse together without destroying the glass or

bleeding the colors. Job took a two-week crash course in the U.S. on glass-making

processes. Glass experts told Job that what he was after was impossible,

so he returned to Xiamen, and after two years of experimenting and developing

new equipment and production techniques, Job was able to produce the collectibles

to Disney’s impossible specifications. From this experience he developed

another of his personal principles:

“Get all the education you can, but don’t fear experimenting.

You may be the first to discover new techniques.”

From Arts Full Circle to Architecture

Meixia is slowly turning from the gift market back full circle to what stained glass was once all about – windows. But Job has innovated there as well.

The size and applications of stained glass windows was limited by their relative fragility and by safety considerations. Job has solved that problem by producing large, custom designed stained glass windows sandwiched between two sheets of safety glass, making the product safe enough for any application, whether industrial or in the home.

One of Meixia’s newest projects is a six meter long

glass window for a new building in Texas. The project amazes architects,

who have never seen anything like it before, and are excited about the

new horizons in design that the technology opens up. Job believes that

just about anything an artist can design he can produce in glass, and

envisions entire glass buildings covered in custom-designed glass vistas.

Yet another potentially lucrative market is custom

designed corporate logos. Meixia has just produced the Starbucks logo

in glass and will present it to corporate heads in the hopes that the

coffee giant will place the stained glass logos in every one of its shops

around the world. With 3,000 North American outlets and 545 international

locations in 19 countries, that’s quite a market.

Job is also contacting designers for hotels and restaurants, and has ideas on the drawing board for stained glass furniture.

Computer-designed and executed stained glass allows Job to create calligraphic designs not possible by hand-cutting alone. He negotiated with a famous American calligrapher to produce a series of calligraphic glass panels, and now he's applying his creativity and technical wizardrly to full-size architectural wonders like the 1st United Methodist Church in Murfreesboro, Tennessee (U.S.A.). The unique Meixia inlaid glass technique was used to create over 800 square feet of Byzantine-inspired stained glass. A newspaper article about the church quoted one person as saying, "We are all pretty overwhelmed by the beauty of it and stateliness of it and all."

Specialization --Helping to Develop West Fujian

One of the big limitations that has accompanied Job’s

striving for newer technology is the increasing overhead. Many orders

for relatively simple products are now not feasible economically because

Meixia increasingly specializes in complex glass products that other glass

companies cannot produce.

To solve this problem, Job is turning to some of his workers’ hometowns

in the remote mountains of Western Fujian Province, where there is little

industry. He brings in groups of workers for 45 days of training, then

sends them back home, where he helps them set up production facilities

with low overhead. This gives him the capability to produce the simple,

labor-intensive products, while helping the economies of the impoverished

mountain villages.

For more information on Meixia, see the website at //www.meixia.com

Supplement

Supplement

To help understand the historical impact

of Bill Job and Meixia (and, happily, Xiamen!), here is an overview of

the development of the glass industry over the past few thousand years.

The Development of the Glass Industry

It seems that everything today is Made in China, and everything yesterday was Invented in China—but glass was a Western invention. Or Middle Eastern, to be exact.

Blue glass found at Eridu dates from before 2200, and a green glass rod found in Babylonia may go back as early as 2600 B.C. But the first glass objects found so far are glass beads from Egypt (2500 BC). The first glass vessels were also made in Egypt, from about 1448 onwards.

Egypt’s unique core-wound glass vessels were built

upon removable clay molds to which a metal rod was attached. A comb-like

instrument was used to coil threads of glass in zigzag, feather or arcade

patterns around the vessel, rolled flush with the surface, and the vessel

was then fired. [Ironically, one of Bill Job’s innovative molding

techniques, which has been adopted by most Asian glass firms, also uses

collapsible molds, proving that the old ways are sometimes the best].

Glass became much more common after 600 BC, and by the 1st century BC

Alexandria was one of the Roman Empires great centers of glassmaking.

Alexandrian artisans used colored glass rods which, when cut across, revealed

a mosaic design. Slices of these canes were placed side by side to form

patterns. This technique, along with a mold technique, was used to produce

glass bowls with an unlimited variety of designs and effects. Colored

glasses were often added so that the product resembled naturally veined

stone, and gold leaf simulated natural pyrites. The bowls were then fire-polished

or polished with spinning wheels fed with abrasives.

Alexandria developed many elaborate techniques, including that of sandwiching

gold leaf designs between layers of clear glass. But it was the development

of glassblowing that helped artisans finally break the molds of the past.

Italy became a glass center by the 1st century A.D., and especially noted

for glass engraving and cameo (etching through a dark glass to a lighter

one sandwiched beneath it). Glass-making then spread to Gaul and Britain

(where it made little impact) and the Rhineland, which became a great

center of glassmaking.

With the fall of the Roman Empire, glassmaking techniques regressed in

the West but continued to evolve in the relatively undisturbed East up

until the time of Islam. Mesopotamia became a center of glass engraving,

and in Egypt, where glassmaking had suffered over the centuries, artisans

developed a technique of stamping glass with patterned tongs. Egyptians

also developed the lustre painting technique, in which a pigment containing

silver was applied to the vessel and fired in a smoky kiln (without oxygen)

to produce a metallic film that varied from pale yellow to brown. Even

today, glassmakers are not sure how some of the polychromatic effects

were produced on the few remaining fragments.

Venice Italy had a glass industry by the 10th century, and became well

known for enameled glass, but Venice’s greatest contribution was

the production of clear, colorless glass, which had been produced earlier

but the secret lost during the middle ages. This glass formed the basis

of the Venetian export industry. By the 16th century, Venetian artisans

were producing glass with complex designs made with white glass threads

embedded in a matrix of clear glass. Venice also developed crackled surfaces

on glass (ice glass) by rolling hot glass onto a bed of glass fragments.

By the late 16th and 17th centuries, Italian glass dominated Europe, but

diamond-point engravers in other nations established unique styles, particularly

in London and Rotterdam. Engravers produced gossamer like drawings and

calligraphy, often accompanying them with Latin or Greek epigrams.

The Advent of Stained Glass

All glass, in theory, is stained glass, colored by the metallic oxides

added during manufacture, but the term stained glass has primarily been

applied to stained glass windows.

The Romans had developed large plates of window glass by the 1st century

AD, and Pope Leo III (795-816) used windows of various colored glass for

St. Paul’s church in Rome.

Initially, colored glass windows were of thin sheets or marble, alabaster,

gypsum, or wooden boards, in which holes were made and fitted with colored

glass. The use of lead to hold the pieces together may date from the 4th

century, though the earliest windows extant are from excavations of sites

dating to the 9th century.

Leading is capable of holding together the most intricately cut pieces

of glass, and thus this technique allowed the artisan’s imagination

to soar, and by the12th century stained glass had become a major art form,

and the most important form of church decoration in Northern Europe.

Early stained glass designs were made by making a full sized design on

a whitewashed board, on which were laid the pieces of glass, cut in intricate

shapes by a red-hot iron tip. A design was then painted on the glass with

a dark enamel pigment containing powdered glass and iron or copper in

a solution of wine or urine. After painting, the carefully numbered pieces

were fired in a kiln to fuse the painted enamels. After the glass had

cooled it was rearranged on the table, and H-shaped strips of lead, cast

in iron or wooden molds, were cut to fit the pieces of glass and soldered

together at the joints. The large windows were made by joining together

smaller assemblies.

Stained glass technique continued to evolve over the centuries, and at

the first World’s Fair, the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851, twenty

five English firms displayed stained glass.

Modern Stained Glass as Art

The first World’s Fair was organized to show off the fruits of the

Industrial Revolution, but the poor artistic quality of machine-made products

inspired the Arts and Crafts Movement, which sought a return to the quality

of handcrafted arts.

Tiffany glass made its debut in Paris in 1894 when Siegfried Bing commissioned

him to produce ten panels designed by the famous artists Bonnard, Ibels,

Vuillard, Graasset, Serusier, Roussel, Vallotton, Ranson, and Toulouse-Lautrec.

Bing’s Salon de l'Art Nouveau in Paris gave us the name for the

movement.

In 1881, Tiffany had filed a patent for a glass with multiple colors mixed

in the same sheet. He and La Farge, the father of opalescent glass, began

producing confetti glass, streamer, ridged, drapery, and glass nuggets

and chunks, and several glass makers began producing many kinds of pressed

glass jewels. In 1889, the Kokomo Opalescent Glass Company won a gold

medal at the Paris World Exposition for their multi-hued window glass.

La Farge experimented with molding distinct objects, like flowers, out

of opalescent glass, and also developed “cloisonné”

glass, a take-off on the ancient Chinese art of cloisonné.

In the 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright made extensive use of stained

glass and opalescent glass in his architecture. The Martin house in Buffalo

has over 100 leaded windows. The great architect Louis Sullivan also used

geometric stained glass, as well as opalescent glass.

Stained glass development declined during the Depression, but in the 60s

the move towards secularism moved stained glass out of the churches and

cathedrals and into the mainstream of architecture and popular culture.

For centuries, the techniques of stained glass were learned only by apprenticeship

to established studios. Positions were few, and only available only to

those who would make stained glass their lifework. But in the 1960s, colleges

and art schools began teaching glass-making techniques, and newcomers

to the art began giving courses and writing how-to books. “Suncatchers”

became popular do-it-yourself projects, and interest mushroomed in stained

glass, as well as repair and restoration of old glass.

As Americans became caught up in nostalgia, Tiffany glass experienced

a revival, and the larger studios began to face the competition of smaller

studios begun by hobbyists—men like Bill Job, in Xiamen.

Note: "Through a glass brightly"

is a play on words on the Biblica verse, 1 Cor. 13:12, "For now we

see through a glass [mirror] darkly [obscure]; but then face to face:

now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known."

Darkly in Greek = ![]()

Back to Top AmoyMagic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

Last Updated October 2006

Faster Access

Outside China,

Click

for Main Menu www.Amoymagic.com

![]()

Daily Use Links

![]()

![]() A.M.ForumJoin

us!

A.M.ForumJoin

us!

![]() RealEstate,housing

RealEstate,housing

![]() Restaurants

Restaurants

![]() Hotel

Guide

Hotel

Guide

![]() Shopping

AtoZ

Shopping

AtoZ

![]() Teach

in China!

Teach

in China!

![]() Study

Chinese!

Study

Chinese!

![]() Doing

Business

Doing

Business

![]() Music

Events

Music

Events

![]() Train

Schedule

Train

Schedule

![]() Bus

Schedule

Bus

Schedule

![]() Darwinian

Driving

Darwinian

Driving ![]()

![]() Medical

Care

Medical

Care

![]() Parks

in Xiamen

Parks

in Xiamen

![]() Sports

in Xiamen

Sports

in Xiamen

![]() Bird

Watching

Bird

Watching

![]() Kung

Fu

Kung

Fu

![]() Bushwalks

(Hikes)

Bushwalks

(Hikes)

![]() Museums

in Xiamen

Museums

in Xiamen

![]() History

of Xiamen

History

of Xiamen

![]() Maps

for download

Maps

for download

![]() Translation

Svcs.

Translation

Svcs.

![]() Festival&

Culture

Festival&

Culture

![]() Xiamen

Univ

Xiamen

Univ

![]() Humor&

Humor&![]() Fun

Fotos

Fun

Fotos![]()

![]() Visa

Info

Visa

Info

Misc. Links

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

To pot?

Dethroned!

To pot?![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]()

Outside China?

Click Here for Faster Access!

Inside China?

Click Here for Faster Access!

![]() A.M.ForumJoin

us!

A.M.ForumJoin

us!