![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

![]() Chinese

Version

Chinese

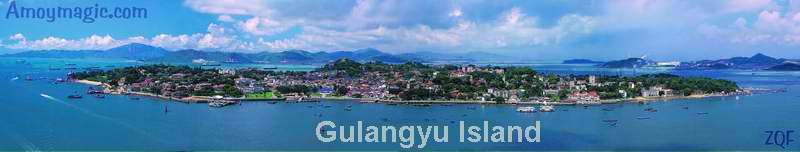

Version ![]() "Gulangyu--Cradle

of Tropical Medicine"

"Gulangyu--Cradle

of Tropical Medicine"

![]() "John

Otte--Missionary Doctor, Architect, Carpenter"

"John

Otte--Missionary Doctor, Architect, Carpenter"

![]() Historic

Hope Hospital

Historic

Hope Hospital

![]() "Sir

Patrick Manson--Father of Tropical Medicine"

"Sir

Patrick Manson--Father of Tropical Medicine"

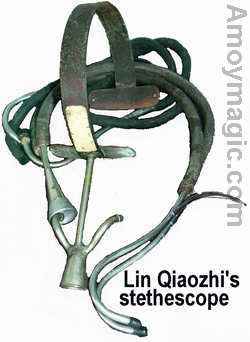

![]() "Madame

Lin Qiaozhi--Pioneer Obstetrician

"Madame

Lin Qiaozhi--Pioneer Obstetrician

![]() "How

Ancient China Discovered (and lost!) Surgery"

"How

Ancient China Discovered (and lost!) Surgery"

“I am a daughter of Gulangyu Islet. In my dreams

I  often

return to the shores of Gulangyu, where the sea is boundless, blue and

beautiful.” Dr. Lin Qiaozhi

often

return to the shores of Gulangyu, where the sea is boundless, blue and

beautiful.” Dr. Lin Qiaozhi

Gulangyu--Cradle

of Tropical Medicine

For such a minor islet, Gulangyu has played a major role in developing

modern medicine. On Gulangyu, “The Cradle of Tropical Medicine,”

Sir Patrick Manson made his great medical

discoveries, and little Gulangyu gave birth to Lin

Qiaozhi, “Mother of China’s Modern Obstetrics and Gynecology.”

Gulangyu’s trailblazing medicine began in 1842 with the arrival

of Dr. Cummings, who lived with Amoy’s

first missionary, David Abeel (Yabili), in

the old home at #23 Zhonghua Rd. The two later moved to Liaozihou and

then to Zhushujiao, where in 1843 they founded a clinic that was forerunner

of “Chibao Hospital” (later part of Hope Hospital).

Gulangyu’s honor roll of medical missionaries includes pioneers

like Dr. J.C. Hepburn (1843-1845), Dr. James Young (English Presbyterian

Mission, 1850-1854), Dr. Hirschberg (London Missionary Society, 1853-1858),

and Dr. John Carnegie (1859-1862). But my favorite of the lot is Dutch-born

American Dr. John Abraham Otte (Yu Yuehan),

of the American Reformed Mission (Guizheng

Jiao).

Back to top

John Otte—Missionary

doctor, architect, and carpenter Dr. Otte not only founded but

also designed and built (with his own hands) three hospitals, including

Gulangyu’s historic Hope Hospital.

During Otte’s copious free time he designed

such Gulangyu edifices as the islet’s most conspicuous land-mark,

the red-domed “Eight Diagrams Building” (Bagualou).

Click

Here for Dr. Otte's story, biographies,

and correspondence.

Click Here for the Hope Hospital Story

Note: On April 28, 2008, Xiamen celebrated Hope Hospital's 110th anniversary by unveiling a statue of Dr. Otte in front of Jimei's new hospital, and issuing a limited series of Hope Hospital stamps, including two with Dr. Otte's image on them! Click Here for more details.

Sir Patrick Manson, Father of Tropical Medicine Gulangyu is known to Western doctors as the “Cradle of Tropical Medicine” because it was here that Sir Patrick Manson (1844–1922), “Father of Tropical Medicine,” made discoveries that helped tackle leprosy, malaria, and other diseases that 150 years ago made Xiamen a “white man’s graveyard.”

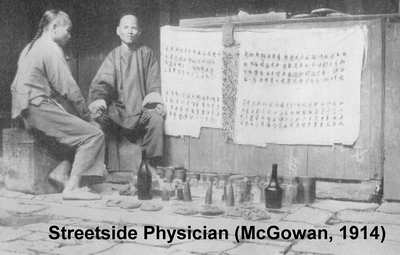

Surgeons or Sorcerers? In his 1873 report of the Amoy Missionary Hospital, Patrick Manson noted that in 1871, it was rumored throughout Amoy that Western doctors gave out magical, poisonous pills that created diseases only they could cure. Pamphlets and posters accused Western doctors of using Chinese’ eyes and hearts for potions, and of drugging and raping Chinese women. When patients died, doctors were accused of murdering them to harvest body parts. When patients survived, doctors were accused of resorting to magic to affect their miraculous cures. In the beginning, theirs was a thankless occupation!

The oldest of nine children, Manson gave up a lucrative career to study medicine. After obtaining his medical degree in 1866 from the university at Aberdeen, he spent 24 years in China, where he tackled not only mosquitoes but also Amoy tigers (he was an avid hunter).

Manson the Tiger Hunter “Life in Amoy in those days in a mixed community of Europeans in China was far from dull. There was a gay social life, and also from time to time sporting events, such as pony races, and shooting expeditions into the surrounding countryside where excellent snipe grounds were provided by the numerous paddyfields.

“Farther field were the wild highlands where every now and again tigers were bagged. Manson was foremost in these adventures and soon gained the reputation of being the best snipe-shot in China.

“But, as he became more familiar with the Chinese and their ways and won their confidence, work began to accumulate.

“Sometimes he was too busy to sleep, as his services were in constant demand.” Sir Philip Manson-Bahr

Locals

were slow to trust the sporting Scotsman. For centuries, Chinese had spread

tales of foreigners eating Chinese babies and using their eyeballs to

line mirrors, and many believed Western doctors’ medicines were

poison.

Manson gained their trust by opening his clinic to the street so everyone

could see that his surgeon’s scalpel didn’t come in a set,

with knife and fork.

Manson was dismayed by Western doctor’s ignorance about the tropical

dis-eases he faced. He estimated 1 in 450 people in Xiamen were lepers,

but Western medicine had no answers. When he asked the British Museum

for information on mosquitoes ; they wrote back six months later to say

they had nothing on mosquitoes but were sending a book on cockroaches

they hoped would help.

When Manson moved to Hong Kong in 1883 he found that Western doctors could

not discern typhoid from malaria, calling it “typho-malaria.”

Malaria had wiped out nearly an entire regiment right after Britain occupied

Hong Kong in 1841, and for years, 3% of British troops died from the dread

disease.

Western

medicine was impotent in the face of tropical disease, and Chinese medicine

fared no better. In 1877, 2% of Xiamen’s population died of cholera,

and to Manson’s frustration, traditional Chinese doctors treated

the disease with alum, stimulants, hot poultices, shampooing, and “pinching.”

But Manson discovered that, in fact, some Chinese treatments did work.

Chinese cured a woman’s anemia with pills concocted from a black

chicken’s dried liver. Western doctors did not learn to treat pernicious

anemia with liver until 1926. Perhaps Chinese medicine’s occasional

successes helped spur the Scotsman on to the research that gave birth

to modern tropical medicine.

Pioneer

or Drunken Scotsman?

In his quest to conquer China’s diseases, Manson

dissected everything from mosquitoes to corpses (in the dead of night,

in graveyards, because Chinese frowned on carving up corpses). But it

was a lonely life, and in 1877 the discouraged young pioneer wrote to

a friend in London,

Pioneer

or Drunken Scotsman?

In his quest to conquer China’s diseases, Manson

dissected everything from mosquitoes to corpses (in the dead of night,

in graveyards, because Chinese frowned on carving up corpses). But it

was a lonely life, and in 1877 the discouraged young pioneer wrote to

a friend in London,

“I live in an out of the world place, away from libraries, out of the run of what is going on, so I do not know very well the value of my work, or if it has been done before, or better.”

In fact, Manson’s

work was so far ahead of his time that other doctors ridi-culed his discoveries.

One doctor said Manson’s claims represented “either the work

of a genius or, more likely, the emanations of a drunken Scots doctor

in far-off China, where, as everyone was aware, they drank too much whisky.”

Manson was first to connect mosquitoes with elephantiasis (1878) and malaria

(1894), and he discovered that only female mosquitoes suck blood (males

live on fruit juices). Manson also invented new surgical techniques and

instruments that even today bear his name (he had one elaborate device

made by a local Chinese metal worker). He also helped introduce modern

vaccination to China—ironically enough, since Taoists inoculated

against smallpox almost 1,000 years ago. Ancient Chinese almost created

surgery as well (see end of this chapter).

As news of Manson’s medical prowess spread, patients flooded in.

In 1871, Manson’s first year at the Baptist Missionary Hospital,

he treated 1,980 patients. His third year he treated 4,476 people. In

1877, he performed 237 elephantiasis surgeries alone. He removed over

one ton of tumors from 61 of the cases and lost only two patients. He

also got sued.

Suing the Surgeon! One patient had so much excess tissue that he could not move and he was carted about town in a wheelbarrow. He made a living selling lemonade and peanuts, and created a table by spreading a cloth over his massive deformities. After Manson removed eighty pounds of tumors, allowing him to move freely once again, he promptly sued Manson and sought compensation. He com-plained that without his convenient table of deformed flesh he had lost his livelihood!

Adapted from Sir Philip Manson-Bahr, “Patrick Manson”

Back to top

Pioneer Medical Educator Manson, like Otte, knew that the way to combat disease was to multiply the medical warriors through medical education. In 1886, Manson established the Hong Kong College of Medicine, which boasted such alumni as Sun Yat-sen, first president of the Chinese Republic. In September, 1898, he opened the London School of Tropical Medicine, although he was adamantly opposed not only by the government but also, ironically, by the medical establishment (which perhaps still suspected his reams of insights were the work of a drunken Scotsman). After writing his bestselling “Manual of Tropical Diseases”, Manson retired in 1912 to fish in Ireland, but returned to medicine at the beginning of World War I, and in spite of debilitating gout, he pursued medical education until his death in 1922.

Madame Dr. Lin Qiaozhi

Pioneer Obstetrician and Gynecologist Over

1000 years ago Chinese women transformed the male Guanyin into the “goddess

of mercy” because male deities lacked compassion for the “weaker”

sex. And male doctors, like male deities, were not especially known for

sympathy with women’s unique needs, so by the twentieth century,

Chinese women were ready for Madame doctor Lin Qiaozhi—a product

of Gulangyu’s pioneering education of women.

Over Lin’s 60-year career she personally delivered over 50,000 children,

and her compassion and dedication won the hearts of men and women alike,

many of whom named babies after her.

Lin was born on Gulangyu Islet on 23rd December, 1901, and grew up at

#47 Huangyan Rd. She always excelled in school, perhaps because her parents

were teachers. She said, “If boys can get a grade of 100, then I'll

get 110!”

A teacher at the Gulangyu Girls Normal School saw Lin crocheting on a

hot summer’s day and said, “You have such great hands. You

should be a doctor!” Lin blushed, but that comment helped set her

course in life.

In 1921, Ms. Lin entered the grueling eight-year program at Beijing Union

Medical College, and earned her doctor of medicine degree from New York

State University (40% of her classmates never graduated). In spite of

her diligence as a scholar she was very easy going, and loved singing

with friends and reading English novels every night until 1 or 2 in the

morning.

In 1932, Lin studied at the London Medical College and the Manchester

Medical College, and the following year toured Vienna on a medical research

trip. Seven years later, she studied in the Chicago Medical College. After

returning to Beijing, she was appointed a hospital’s director of

obstetrics and gynecology--the 1st woman in China to have such a position.

Lin Qiaozhi never married but was close to her extended family. Her brother,

Lin Zhenming, financed her studies at Beijing Union Medical University,

and after her graduation she footed the bill for her older brother’s

four children to attend Yanjing University. After liberation, she made

a list of her relatives in Fujian and sent money to them until she passed

away.

Dr. Lin was a model teacher, as well as writer and editor of such books

as “Advice on Family Health.” She also chalked up many firsts.

In 1955, she became the first female member of the Learned Department

of Academia Sinica. In 1956, she was appointed vice-chairwoman of the

China Medical Association. In 1959, she took up the position of director

of the Beijing Maternity Hospital, as well as deputy director of the Chinese

Academy of Medical Sciences.

In 1978, Lin became vice chairwoman of the National Women’s Federation

of China, and visited four West European countries as the deputy head

of the Chinese People’s Friendship delegation. But while in Britain,

she suffered a brain hemorrhage, and was hospitalized for half a year

before returning to China.

In 1980, Dr. Lin suffered another hemorrhage. On April 22nd, 1983, she

passed away at the age of 82, having devoted her entire life to thousands

of mothers and babies at the Beijing Union Medical College Hospital and,

indirectly, to millions of women and children throughout China.

In 2001, famous doctors and prominent health officials and government

leaders gathered in Beijing to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Lin’s

birth. Officials unveiled a copper statue of the doctor, and announced

the new Lin Qiaozhi gynecological and obstetrics research institute at

the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Premier Li Peng wrote an inscription

that reads, “Forever cherish the memory of outstanding medical scientist,

Lin Qiaozhi.”

Learn more about Dr. Lin at the Lin Qiaozhi Memorial Hall on Zhangzhou

Road, just past Fuxing church. This beautiful garden, with its sculptures

of children and white marble statue of Lin, was built the year after Dr.

Lin passed away, in 1984. The Exhibition Room tells her life story. A

row of stone “books” along Zhangzhou Rd. shares such Lin quotes

as:

“During the times I am not working, I feel lonely and isolated and

as if life has no meaning.”

How Ancient China Discovered (and lost!) Surgery

(From McGowan, 1913, pp.176-9)“…There was not a doctor in the Empire who knew anything of anatomy and for any one of them to have performed a serious surgical operation would have meant certain death to the patient. [But]…

“Tradition tells the story of one famous doctor [Huatuo], who lived in the misty past, and whose prescriptions form part of the medical library of every regular practitioner, that is intensely interesting. He seems to stand out more prominently than any of the others who have become conspicuous in the history of medicine, because he evidently had the ambition and perhaps the genius to inaugurate a new system in the treatment of diseases. He evidently felt there were occasions when the knife ought to be used if life were to be saved.

“On one occasion a military officer had been severely wounded in the arm by a poisoned arrow in a great battle in which he had taken part. The doctor, who for long centuries has been a god, and shrines and temples have been erected in which his image sits enshrined, was summoned to his assistance. He saw at a glance that unless heroic measures were at once adopted the man would die of blood-poisoning.

Contrary to the universal practice then in vogue, he cut down to the very bone, extracted the arrow, and scraping away the poison that might have been injected into the flesh, he bound up the gaping wound, using certain soothing salves to assist Nature in her process of healing.

“The result proved a great success, and might have been the means of introducing a new era in the treatment of diseases throughout China.

“Not long after a high mandarin [Caocao], who had heard of the wonderful cure, summoned the same doctor to prescribe for him. He had been greatly troubled with pains in his head, and no medical man that had attended him had been able to give him any relief. His case having been carefully diagnosed, the doctor proceeded to tell him what he thought ought to be done.

“I find,” he said, “that what really is the matter with you is that your brain is affected. There is a growth upon it, which, unless it is removed, will cause your death.

Medicine in this case,” he continued, “will be of no avail. An operation will have to be performed. Your skull must be opened, and the growth that is endangering your life must be removed.

“The thing, I think, can be safely done, and your health will be perfectly restored, and you may continue to live for a good many years.

“If you are pleased to confide in me, I have full confidence in myself that I can do all that is needed to restore you to perfect health.

“Whilst he was talking a cloud had been slowly gathering over the mandarin’s face. His eyes began to flash with excitement and a look of anger to convulse his face. In a voice tremulous with passion, he said: “You propose to split open my skull, do you? It is quite evident to me that your object is to murder me. You wish for my death, but I shall frustrate that purpose of yours by having you executed.” Calling a policeman, he ordered him to drag the man to prison, whilst he gave orders to an official who was standing by that in ten days hence the doctor should be decapitated for the crime of conspiring against his life.

“During the days he was in prison he so won the heart of the jailer by his gentleness and patience that he showed him the utmost devotion and attention. The evening before his execution, he handed over to him some documents that he had been very carefully preserving, and said, ‘I am most grateful to you for the kindness you have shown me during the last few days. You have helped to relieve the misery of my prison. I wish I had something substantial to give you to prove to you my appreciation of the sympathy and tender concern you have manifested towards me.

“’There is one thing, indeed, that I can bestow on you, and that is the manuscripts of all the cases I have attended. These,” he said, handing them to the jailer, “will raise your family to wealth and honor for many generations yet to come. They explain the methods I have employed in the treatment of disease. Never part with them; neither let the secrets they contain be divulged by any of your posterity, and so long as your descendants are faithful to them poverty shall never shadow the homes of your sons and grandsons nor of their children after them.’

“Next day this great medical genius was foully put to death merely to satisfy the caprice of an ignorant official, and the first dawn of surgical enterprise was eclipsed by his death, and many a tedious century would have to drag its weary way along before the vision that had died out in blood would again appear to deliver the suffering men and women of China.”

![]() Favorite

Fujian Sites

Favorite

Fujian Sites ![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album ![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Fujian

Guides

Fujian

Guides ![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Wuyi

Mtn

Wuyi

Mtn ![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Taimu

Mtn.

Taimu

Mtn. ![]() Roundhouses

Roundhouses

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Jiangxi

Jiangxi

![]() Guilin

Guilin

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Readers'

Letters

Readers'

Letters

Last Updated: May 2007

![]()

DAILY LINKS

![]() FAQs

Questions?

FAQs

Questions?

![]() Real

Estate

Real

Estate

![]() Shopping

Shopping

![]() Maps

Maps

![]() Bookstores

Bookstores

![]() Trains

Trains

![]() Busses

Busses

![]() Car

Rental

Car

Rental

![]() Hotels

Hotels

![]() News

(CT)

News

(CT)

![]() Medical

& Dental

Medical

& Dental

![]() YMCA

Volunteer!

YMCA

Volunteer! ![]()

![]() XICF

Fellowship

XICF

Fellowship

![]() Churches

Churches

![]()

![]() Expat

Groups

Expat

Groups

![]() Maids

Maids

![]() Phone

#s

Phone

#s

EDUCATION

![]() Xiamen

University

Xiamen

University

![]() XIS(Int'l

School)

XIS(Int'l

School)

![]() Study

Mandarin

Study

Mandarin

![]() CSP(China

Studies)

CSP(China

Studies)

![]() Library

Library

![]() Museums

Museums

![]() History

History

DINING

![]() Restaurants

Restaurants

![]() Asian

Asian

![]() Veggie

Veggie

![]() Junk

Food

Junk

Food

![]() Chinese

Chinese

![]() Italian

Italian

![]() International

International![]()

![]() Visas

4 aliens

Visas

4 aliens

RECREATION

![]() Massage!

Massage!

![]() Beaches

Beaches

![]() Fly

Kites

Fly

Kites

![]() Sports

Sports

![]() Boardwalk

Boardwalk

![]() Parks

Parks

![]() Pets

Pets

![]() Birdwatching

Birdwatching

![]() Kung

Fu

Kung

Fu ![]() Hiking

Hiking

![]() Music

Events

Music

Events

![]() Festival&Culture

Festival&Culture

![]() Humor&

Humor&![]() Fun

Fotos

Fun

Fotos![]()

BUSINESS

![]() Doing

Business

Doing

Business

![]() Jobs!(teach/work)

Jobs!(teach/work)

![]() Hire

Workers

Hire

Workers

![]() Foreign

Companies

Foreign

Companies

![]() CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

![]() MTS(Translation)

MTS(Translation)

![]()

Back to Top