![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

"Chinese

Beauty,"

"Chinese

Beauty,"

by Prof. Kazimierz Poznanski

Click

Here to E-mail Dr.

Poznanski

7050 50th Ave. NE Seattle, WA 98115

Click

Here to view Prof. Kaz'

biographical page.

Click Here to read Dr. Kaz' "Happy

Places" (About Teng Hiok Chiu)

Click Here for Teng

Hiok Chiu Biographical Page

Click Thumbnails Below (yellow-framed)

for larger images

CHINESE BEAUTY, by Kazimierz Z. Poznanski

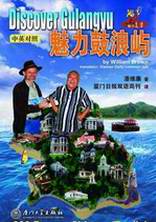

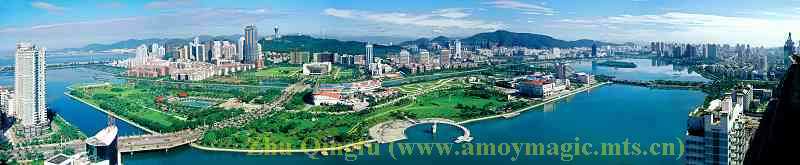

I grew up in Poland in an artistic family but when the time arrived for me to decide on my education I chose something very un-artistic – economics. Eventually I became a university professor of economics in the United States where I moved in 1980. But I always kept my connection with art, initially mostly through collecting paintings only to quickly turn to painting as an essential part of my life. The greatest impact on my artistic life had a single discovery in 1992. About ten years ago, by sheer luck, I discovered a completely forgotten Chinese-American modernist painter Teng Hiok Chiu (1903-1972). Raised on Gulangyu Island, outside of Xiamen, Chiu might easily be one of the

best oil painters of his generation of the first Western-trained Chinese artists. In a recent interview Michale Sullivan, the foremost professor of China’s art history from Oxford stated that Chiu is the best Western-style, meaning using oil landscape painters of this early period.

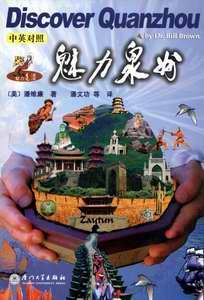

Back to topIn 2004, I came to Xiamen to visit Chiu’s hometown and discuss Chiu’s works with local artists, who almost without any exception, were amazed by this discovery. Very much the same has been the reaction by other artists in such places like Beijing and Chengdu. I am amazed with this discovery as much as my Chinese counterparts. To be frank, I neither had any real understanding nor had I been interested in Chinese painting before I found first Chiu’s. In fact, few Westerners have the courage to cross the cultural barrier and to develop real appreciation for Chinese painting. In addition, the people of the West people give even less attention to Chinese oil painters than to the traditional painters working in ink. It is generally assumed that Chinese artists using Western techniques are just imitating instead of creating original art. However, I was quite taken by the beauty and harmony of these first Chiu’s oil paintings, without thinking whether they are original or not. The beauty and harmony that I found in these paintings was more or less what would draw me to other, non-Chinese works in my collection daring from more or less same period. But from the very beginning I felt that there is something that I like so much about Chiu’s works but have no way of defining it. And this special quality of his paintings was quite different to what I was used to see in Western artwork of his contemporaries.

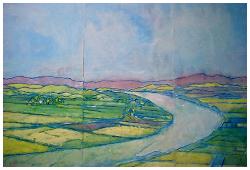

Back to topEventually Chiu made me first study Chinese art history from the books for me to get an understanding of the traditional Chinese painting techniques. Unlike most of collectors who simply enjoy paintings on their walls I also wanted to think the way Chiu thought and to feel what he felt. Thus I also became a careful student of Taoist and Confucian philosophy and only then I began to appreciate the old ink scrolls. I soon also began to really appreciate the incredible sophistication of Chinese art tradition. Namely, that this art is about life, and that it is about life since both philosophies behind it are about life. And that in these two philosophies nature is life, and for this reason art is also about nature, specifically about landscapes, not the views of some specific places but almost endless panoramic vistas, since nature knows no limits. The nature, as understood in both philosophies, is based on a moral order that holds together in harmony two basic elements, yin and yang. In painting these two elements are symbolized by water, a s a female yin, and mountains, or mail yang. Teng Hiok Chiu was always aware of these philosophical roots of Chinese painting and this is why, while focusing on landscape he also preferred landscapes that bring water – river, sea, waterfall or mist – and mountains together. And, when he was painting places outside of China, where he spent two-third of his lifetime, they would be at least in some way reminders of his native China, particularly Gulangyu Island.

Back to topIt is also Chiu who made me go to China and it is the beauty of China, with its vast plains, poetic ridges, ancient villages, blue roofs and lush greenery, that made me even more interested in Chinese culture. Only then, with the knowledge from the books and personal appreciation of the land of China, I have fully realized that behind the Western visual of Chiu’s paintings there is Chinese meaning and that it is this Chinese meaning that makes his art so special. By the time I first visited China searching for traces of Chiu’s life I already had a large group of black and white charcoal drawings by myself, mainly large Chinese-style landscapes. After seeing numerous scrolls, I was simply drawn into this world and one day my hand switched away from what for years I used to do on paper and instead it started drawing such Chinese-style landscapes. When in 2001, in Chengdu I showed my group of drawing to a local painter only to be few days later invited to show all of them at the downtown Sichuan Art Museum. At the opening of my exhibition I gathered a lot of comments, including the opinion that my charcoal line is very Chinese, since it is free handed and flowing line, and thus it is full of life. I easily realized the significance of this comment, namely that while Chinese traditional painting is all about life only this kind of line – free handed and flowing – is reflective of life, with its continuity and volatility.

The same painter handed over to me three boxes of water-based Chinese paints, eleven of his used brushes and hundred sheets of rice paper. All of this was of course new to me and I had no idea how to use these unexpected gifts. Since then I moved away from doing basically black and white Chinese-style landscapes to focusing on color. This how, with the helping hand of Chiu, I turned completely Chinese-style color landscapes and gave up my earlier color landscape efforts. It was thus Chiu who made me a painter that I am now, or more precisely it was him who helped me to discover my special desires earlier than it would had happened otherwise. While Chiu moved to the West to learn Western techniques to express Chinese philosophy, he made me move to China to instill same Chinese meaning to my Western art. He produced his own fusion of Western and Chinese expression living in a foreign country away from his native land, same way as myself, also an emigrant, similarly stretched between two cultures, native and foreign one. Chiu left for the West because he felt that his Chinese culture sets unacceptable limits on his creative drive, while I have turned to China to rescue myself from within limits imposed on me by the Western culture.

Back to topOne element of Chinese tradition that Chiu was unable to abandon in his search, without destroying himself, was the typical of Chinese tradition very happy perspective on life – belief that life is a blessing and that anybody can find real fulfillment by finding harmony with the rest of nature – that makes some Westerns gladly embrace Chinese art tradition. This is particularly the case with Westerners who independently develop their own happy attitude towards life and striving for harmony in their own life. It could well be that this is who I am and why I find it so easy to identify with Chinese art tradition. This is why it is so easy for me to follow in my art most of the principles of traditional Chinese painting so helpful in delivering the philosophical message that we, humans, are only small part of it. This is why, like Chiu, I prefer to paint large-scale mountain and water landscapes, many from places that I have visited in China myself. When I see some specific places I never paint them the way they are but simply take a sketch. This sketch is to register the

structure of the place and not the detail, and when I try to copy my sketch I make some changes, and when I eventually do my painting, I move away from the sketch even more. So, at the end what is painted is a distant image of the places I visited.

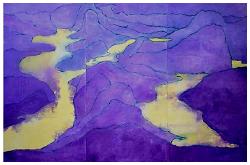

Back to topMy landscapes are also made to capture the essence of nature, seen as a moral order, under which no element alone – yin or yang – can create life; for this they need each other and what brings them together is the highest form of harmony – love. And, this is exactly the feeling that my paintings contain, though I do not fill my paintings with love on purpose – this comes to me naturally. Accordingly to the Chinese tradition I use line as the basic element of constructing my paintings, with flat areas within outlines. Also similar to Chinese tradition, my paintings use a limited range of color but it is also true that I never use black and white, but rather a combination of red and yellow, or blue and green. I know that in Chinese tradition, black and white are seen as the best reflection of the two elements – yin and yang, but my alternative color combinations are to me the same symbols of female yin and male yang. And this duality is also reflected in the combination of two qualities of my paintings, namely that my landscapes are at the same time soft and strong, or in other words -- mute and passionate. And, unexceptionally, I only show the splendor and beauty of nature, trying to take the viewer to the invisible, where the life spirit resides, something that Chiu was so skillful about.

Surely, in many ways my paintings depart from the Chinese tradition, not just because I do not use black and white combinations. For instance, I am aware that in the Chinese tradition it is the sign of greatness when a painter touches the paper with brush only once. So, the artists train endlessly to finally be able to use only one stroke to accomplish complete expression of what they want to convey on paper. Myself, I usually use multiple layers of paint and I go on correcting my lines many times. But when I put the final touch, my feeling is, that it is very much the same as the first – and final- touch by those who totally stick to the Chinese canon. Anyway, whether it is the first touch that makes your painting best or the last touch that that makes your painting best, one needs to be able to reach real mastery to makes the painting look – or mean – the best.

Back to topI haven’t received any regular professional training in Chinese art before and there might be some mistakes in the way I use brush and paint, but I don’t worry about that too much. The few sessions in the studios of my Chinese friend artists have been very important to me but surely not enough to substitute for a rigorous education. It is true, however, that I have learned a lot about Chinese painting by living together with Chiu’s art for so many years. Interestingly, this experience of mine as a painter is not so different from a traditional Chinese painter, called literati, who would collect art – old scrolls – to study masters and who would learn painting this way on their own without a real teacher. So, technically speaking a painter of this sort would be an amateur, but still he could become a master for the generations to come after.

But my feeling is that with rigorous education or not, as long as I am able to grasp the essence of Chinese traditional painting, the harmonious and happy moral world it renders, my painting is truly a Chinese painting. And, importantly, with this attitude, I can freely use whatever elements of Chinese tradition I like most with any elements of Western-style painting that I find useful to execute a particular painting. This way I am able, I think, to be most creative and hopefully push the Chinese art idiom forward to make it more modern, same way Chiu tried during his lifetime. The greatest reward for my work with Chinese art tradition is that my paintings are easily recognized by my Chinese friends for their Chinese essence. I found it out, for instance, during my March 2004 individual exhibition at Xiamen Municipal Gallery at the Palace of Culture. Or more recently when I showed my landscapes to an artists from Chengdu who said to me that while my works look so much Western they have all the distinctive characteristics of Chinese traditional painting – they are peaceful, they take the viewers to a different – outer – world and they are also high minded, or -- to use other words – they are done in a high spirit of noble intentions.

Back to topGiven this reception, it could be that one day my landscape paintings might find their way to the mainstream of Chinese contemporary art, itself in search for a new identity. There are two extremes in Chinese painting nowadays. One is the younger generation of artists many of whom are trying to literally copy from the most recent Western art works, which so often are filled with anger, pessimism, obscenity and distraction. While exploring this artistic venue, they are usually unconscious of losing the essence of China’s traditional art heritage with its special moral message – calling for acceptance, optimism, elegance and balance. The other group is the one that follows the Chinese art tradition mainly by carefully sticking to the old masters but this is not going to succeed in preserving the essence of this art from the invasion of the Western-based art. A very important curator of Chinese contemporary art from Hong Kong, Johnson Chang, is one of those who want to preserve Chinese – or rather Asian – art tradition, with its own charm and wisdom, while catching with the rhythm of our modern times.

I also think that one must find a way somewhere between these two mentioned above extremes and Teng Hiok Chiu surely provides a perfect example for us of this kind of approach. He successfully maintained his Chinese culture by masterfully using Western means of expression. This is what I am trying to accomplish by following his art but also by moving beyond it and taking – as well-known art professor Wang Zhong from Beijing pointedly remarked – a simpler, broader and more general approach. Whatever the differences between Chiu and myself we share the same attitude that doing art is a form of a mission and that a purpose of art is to display the joy, the joy of life – when living follows the art of living in harmony with the rest of the world.

Back to topBut art is also about the working of the mind, since the visual harmony requires mental discipline. Even if art is driven by a feeling of love, as it should be, the mind has to find the bets way to convey your attitude. And, what I have learned form my painting of Chinese landscapes done Chinese way is that art requires very much the same skill as economics, namely that in both cases you have to solve some equations. Even when you make your first stroke it is not easy since you have to relate it to the empty space of the whole piece of rice paper. And when you make your second stroke you have to relate it to the previous one and the further you go the more variables – stroke – you have to include in your equations, and at the end this becomes almost an impossible job to handle. And those who last till the end and find the final mathematical solution are the best artists. It might well be that the reason the traditional Chinese painter, the literati, had to be not only a collector of art but also, or primarily, a scholar, a person with an adept mind, is that painting is indeed about solving equations the way economists do it. It is this concept

of painter, who is also a scholar and a collector that should not be lost in the current efforts to modernize Chinese art while preserving its centuries of refinement and splendor.

Preserving is not the Western approach but a Chinese approach. In Western culture the focus is on change – experimentation – as a source of progress in art or in other fields of human activity. But if a culture reaches its best, refine form, with right philosophy of life and the right way to express this way in art, what is there to change. Changing the best possible, or near-perfect leads to regress – or even destruction. And if China has already developed such refine culture there is really no reason to change it but at best to make some modifications. Under these conditions, it is lack of change, keeping in line with the tradition, that is the only reasonable approach. And, one has to keep in mind that it is easier to change than to keep things the old way. It could well be that the greatest feature of Chinese Culture is its ability to do the difficult thing – to keep things the traditional way and avoid temptation of doing what is easy – reject the past and seek change.

Back to top

“A good traveler is one who does not know where

he is going to, and a perfect traveler does not know where he came from.”

Lin Yutang

Back to top

![]() Favorite

Fujian Sites

Favorite

Fujian Sites ![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album ![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Fujian

Guides

Fujian

Guides ![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Wuyi

Mtn

Wuyi

Mtn ![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Taimu

Mtn.

Taimu

Mtn. ![]() Roundhouses

Roundhouses

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Jiangxi

Jiangxi

![]() Guilin

Guilin

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books

![]() Readers'

Letters

Readers'

Letters

Last Updated: May 2007

![]()

DAILY

LINKS

![]() FAQs

Questions?

FAQs

Questions?

![]() Real

Estate

Real

Estate

![]() Shopping

Shopping

![]() Maps

Maps

![]() Bookstores

Bookstores

![]() Trains

Trains

![]() Busses

Busses

![]() Car

Rental

Car

Rental

![]() Hotels

Hotels

![]() News

(CT)

News

(CT)

![]() Medical

& Dental

Medical

& Dental

![]() YMCA

Volunteer!

YMCA

Volunteer! ![]()

![]() XICF

Fellowship

XICF

Fellowship

![]() Churches

Churches

![]()

![]() Expat

Groups

Expat

Groups

![]() Maids

Maids

![]() Phone

#s

Phone

#s

EDUCATION

![]() Xiamen

University

Xiamen

University

![]() XIS(Int'l

School)

XIS(Int'l

School)

![]() Study

Mandarin

Study

Mandarin

![]() CSP(China

Studies)

CSP(China

Studies)

![]() Library

Library

![]() Museums

Museums

![]() History

History

DINING

![]() Restaurants

Restaurants

![]() Asian

Asian

![]() Veggie

Veggie

![]() Junk

Food

Junk

Food

![]() Chinese

Chinese

![]() Italian

Italian

![]() International

International![]()

![]() Visas

4 aliens

Visas

4 aliens

RECREATION

![]() Massage!

Massage!

![]() Beaches

Beaches

![]() Fly

Kites

Fly

Kites

![]() Sports

Sports

![]() Boardwalk

Boardwalk

![]() Parks

Parks

![]() Pets

Pets

![]() Birdwatching

Birdwatching

![]() Kung

Fu

Kung

Fu ![]() Hiking

Hiking

![]() Music

Events

Music

Events

![]() Festival&Culture

Festival&Culture

![]() Humor&

Humor&![]() Fun

Fotos

Fun

Fotos![]()

BUSINESS

![]() Doing

Business

Doing

Business

![]() Jobs!(teach/work)

Jobs!(teach/work)

![]() Hire

Workers

Hire

Workers

![]() Foreign

Companies

Foreign

Companies

![]() CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

![]() MTS(Translation)

MTS(Translation)

![]()

Back to Top