![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

(Contact Dr. Kaz for more info)

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

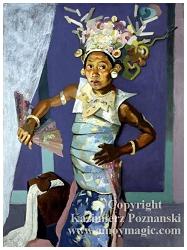

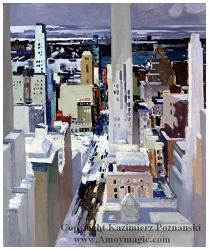

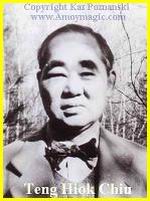

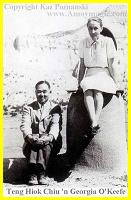

"Happy

Places: Landscaping by Teng Hiok Chiu"

"Happy

Places: Landscaping by Teng Hiok Chiu"

by Prof. Kazimierz Z.Poznanski

Click Here

to E-mail Dr. Poznanski

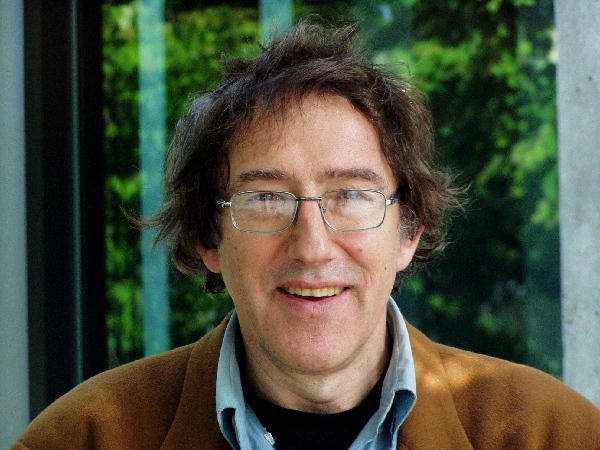

Kazimierz Z. Poznanski, Professor

Jackson School of International Studies

PO Box 353 650

University of Washington

Seattle WA 98195

Note: Dr. Kazimierz Z. Poznanski, a professor  of

economics at the University of Washington, Seattle, has also taught at

Cornell and Northwestern Universities. He has published books with the

University of California-Berkeley and Cambridge University Press. A long-time

collector of paintings from the modernist period, Poznanski has spent

much of the last ten years focusing on Chinese painting,, particularly

the art of Chinese-American Teng Hiok Chiu (1903–1972)

of

economics at the University of Washington, Seattle, has also taught at

Cornell and Northwestern Universities. He has published books with the

University of California-Berkeley and Cambridge University Press. A long-time

collector of paintings from the modernist period, Poznanski has spent

much of the last ten years focusing on Chinese painting,, particularly

the art of Chinese-American Teng Hiok Chiu (1903–1972)

Note: All

text and images below, and on Prof. Kaz' page,

are from Prof. Kaz's research, and his book, "Path of the Sun--The

World of Teng Hiok Chiu, The Kazimierz Z. Poznanski Collection."

Click Thumbnails Below

(yellow-framed) for larger images

Click Here for Teng Hiok Chiu Biographical

Page

Click Here for "Chinese

Beauty," (about Prof. Kaz' artistic journey, with images of his

unique interpretation of Chinese art)

Click Here for "Feeling China: Art as

Jazz," by Dr. Kaz

[Note: Xiamen is now one of the planet's leading producers of original and reproduction oils! Check out this website: Amoy Paintings International!]

“Is

it extravagant hope to think that the artist may be the first to teach

mankind to think together and to follow the same truth and righteousness

by learning to appreciate the same beauty?” “Since I used

to play amidst the beautiful temples and pine trees or on the sandy beach

I have wanted to appreciate the best in nature and to be able to help

everyone else to do so. As soon as I got an opportunity to travel, I went

far and wide throughout my own country to see the best that China had

in paintings, architecture and scenery. This led me to a study of art,

but hitherto I had known nothing about its history, or of its practice,

except in Chinese writing, which is really painting.” “I found

I could not learn what I wanted from the artists of China itself, and

so I was driven to the West. My aim at first was just to acquire the technique

of Western art, but I found there was more in it than that. In England

and on the Continent of Europe a far wider vision of what art really is

has opened up before me. As I go forward I realize increasingly that neither

East nor West, and that some day there must be the Art of the New World

Civilization, to creation of which, as painter, I wish to contribute.

Art is a universal language which speaks to every human heart” Teng

Hiok Chiu

“Is

it extravagant hope to think that the artist may be the first to teach

mankind to think together and to follow the same truth and righteousness

by learning to appreciate the same beauty?” “Since I used

to play amidst the beautiful temples and pine trees or on the sandy beach

I have wanted to appreciate the best in nature and to be able to help

everyone else to do so. As soon as I got an opportunity to travel, I went

far and wide throughout my own country to see the best that China had

in paintings, architecture and scenery. This led me to a study of art,

but hitherto I had known nothing about its history, or of its practice,

except in Chinese writing, which is really painting.” “I found

I could not learn what I wanted from the artists of China itself, and

so I was driven to the West. My aim at first was just to acquire the technique

of Western art, but I found there was more in it than that. In England

and on the Continent of Europe a far wider vision of what art really is

has opened up before me. As I go forward I realize increasingly that neither

East nor West, and that some day there must be the Art of the New World

Civilization, to creation of which, as painter, I wish to contribute.

Art is a universal language which speaks to every human heart” Teng

Hiok Chiu

Back to top

Happy Places

by Dr. Kazimierz

Z. Poznanski

To

me, the most special quality of Chiu’s art is that it is all about

happy places, filled with grace and beauty. It could be that this reflects

Chiu’s predisposition, but I would argue that the reason why the

painter almost always showed a sunny side is because he largely worked

in the Chinese art tradition. This is a tradition in which the entire

world is viewed as a happy place and where being alive means being happy.

The role of art is to project such truth and this is exactly what drove

Chiu’s work as a modernist painter.

To

me, the most special quality of Chiu’s art is that it is all about

happy places, filled with grace and beauty. It could be that this reflects

Chiu’s predisposition, but I would argue that the reason why the

painter almost always showed a sunny side is because he largely worked

in the Chinese art tradition. This is a tradition in which the entire

world is viewed as a happy place and where being alive means being happy.

The role of art is to project such truth and this is exactly what drove

Chiu’s work as a modernist painter.

The fact that there is substantial influence from the Chinese tradition

on Chiu’s art might initially seem counterintuitive, since, at first

examination, his work appears surprisingly Western. Importantly, Chiu

received his formal artistic training not in China but in the United States

and Europe. However, it is also true that Chiu obtained a thorough general

education in China and that he was exposed to many objects of Chinese

art in the house of his affluent parents. His was a very distinguished

and educated family of merchants. Typically, in such a family, each generation

would accumulate scrolls for viewing and numerous decorative pieces, such

as porcelain vases. Chiu himself owned such a collection, most likely

built upon some of the art objects taken from his family.

Back to top

It is also a fact that it was in the West that Chiu first began a serious

study of Chinese art, specifically in London. Immediately after his graduation

from the Royal Academy of Arts, he was offered a position by Lawrence

Binyon, the Curator of the Chinese Collection at the British Museum. He

spent almost two years under the personal mentorship of Binyon. During

this time he had the opportunity to see and learn about some of the best

Chinese paintings. One can hardly imagine a more appropriate introduction,

since Binyon was not only one of the foremost experts in the field but

also a passionate admirer of Chinese art tradition. He did not hesitate

to compare China with Greece and went even as far as saying that in some

ways the former exceeded the latter.

THE SPIRIT OF ART

That Chinese art is different from other types of art, including Western

art, stems from the fact that it developed a specific outlook on the world.

The Chinese perspective reaches back to the earliest stages of history,

where the world was conceptualized as nature, and where nature meant life.

The world is seen as a complex living system, and life is a dynamic process,

without either a definite beginning or a certain end. Life is an attribute

of everything because nature is a unity that cannot be broken up in any

place without instantly destroying all of it. In this tradition, it is

not only that people and animals have life, but also that rocks have life

as well. By continuously holding onto this basic message, Chinese worldview

has never become really modern.

Another important element in the Chinese worldview is seeing nature in

moral terms. Nature is believed to follow a certain moral order, through

which all of its components relate to each other and allow for the life

process to continue. In stating that moral order is the attribute of nature,

the Chinese worldview rejects the notion that the life-rules could be

invented either by mortal people or by immortal gods. For this reason,

the only legitimate way to arrive at a moral code that would be suitable

for people is to carefully examine nature. This role was ascribed to art,

so that art became also the source of moral guidance – it turned

into the art of living. In this way, art in China has slowly evolved into

the foremost vehicle for conveying to society their sense of morality.

Back to top

This specific role of art was codified several hundred years ago in the

late Sung dynasty and then elaborated upon under the Ming dynasty, when

the model of an artist, called “literati,” entered the tradition

(see: Sullivan, 1984; also Cotter, 2002). At this turning point the underlying

principles of the traditional Chinese art canon were specified as well.

The literati were scholars, collectors, and painters all in one person,

which aspired to give expression to the moral order through images and

poetry. This person, central to the whole working of a society, had to

be a scholar to fully understand the message, a collector to study the

message by examining the past, and a painter to use the brush to be a

teacher who conveys the principal moral message about nature.

Significantly, those working in the Chinese tradition do not hide their

mission but are quite explicit about their moral agenda, mixing words

of wisdom with images of the same wisdom. To make sure that the moral

message is not lost, artists use a portion of their painting to deliver

their primary lesson in some carefully crafted calligraphy, usually in

the form of a poem. The connection between the two is very intimate, since

the calligraphy – using the same medium, ink -- is seen as a form

of painting and indeed is such a form. Moreover, the whole painting, scroll

on paper, is seen as a form of poetry. with the difference being that,

unlike the written words of a poem, painting with its own visual images

is just a mute poetry (see: Sickman and Soper, 1968; also Chaves, 2000).

Back to top

The key moral message in Chinese tradition is that the world is a happy

place. What is meant by happiness is the full experience of life, as something

more precious, or rewarding than anything else. It is not the kind of

happiness that comes from having good time, or enjoying physical pleasures,

but rather the kind that comes from gaining an inner balance and finding

a communion with the nature – it is an affair of the heart not of

the body. As such, happiness, or being happy is within the reach of any

human being as part of the universal flow of life, or nature. Therefore,

the central message of Chinese tradition is that one could, and should,

make oneself happy by humbly embracing the splendid – and inherently

wise -- nature with its eternal rules and also with its diversity.

To say that the world is a happy place, as is the case with Chinese tradition,

does not mean, however, that it is an absolutely perfect place. To the

contrary, this world is largely imperfect; it is a happy place, with the

imperfections. Of all the imperfections, it may seem that getting older

and ultimately facing death is the one that might be considered the worst.

To the contrary, in the Chinese tradition the passing of time and the

parting with this world is seen as a part of life - both are accepted

as inevitable. It was none other than Chiu’s mentor, Binyon, who

stressed that given the above view, Chinese art is construed as a vehicle

for projecting the message of happiness. He would go further and say that

indeed to show the happy side of human beings is the only mission in art.

Furthermore, what defines a happy place in the Chinese tradition is the

presence of harmony. This is because life would not be possible without

harmony, which presumes good feelings – compassion -- between various

beings. In fact, life requires birth, and birth would be impossible without

the utmost good feeling without putting the life of another – new

-- being above your own, a choice to be made only out of the utmost good

feeling -- that of love. It is this sense of goodness, or even loving,

what makes the world a living unity, and it is this sense that truly represents

world’s vital spirit, as understood in Taoism . And, at its deepest

level, the purpose of Chinese art is to explain life is a product of a

vital spirit, which is about allowing good, or love, to rule.

Back to top

THE ART OF SPIRIT

This basic moral message, focused on the life-flow and life-rules, has

become an organizing principle for Chinese art. Not only is composition

subordinated to this message, but so is symbolism and the techniques,

all built into a system. In this respect, Chiu cannot

be considered a truly traditional Chinese artist, but rather as somebody

who, quite consciously, or deliberately,works within this tradition. While

he fits this tradition in terms of showing the world as a happy one, where

there is harmony, it is not the case hat he always uses every element

of the Chinese artistic vocabulary to deliver this message. Most of the

time Chiu would simply utilize some elements of this approach, and, even

then, he would transform them in a way that best fits his other needs.

The reason why Chiu concentrated almost exclusively on landscape was because,

in the Chinese tradition, this genre is found to be the most suitable

for expressing the moral truth. In this setting, artists are able to fully

express the notion that the world is about spirit – heaven -- and

matter – earth -- as two inseparable parts of the world. Heaven

is on earth, so that when earth is painted, so is heaven, but while earth

is visible haven is not visible, and for this reason Chinese painter cannot

simply be a photographer of a landscape. Such artist is, so to say, a

landscaper, a gardener who has to compose a landscape according to own

vision of heaven, one that creates meaningful spaces to transpose this

vision onto those that would find their work engaging enough to pause

for reflection.

And, no doubt, Chiu was a landscaper, and remarkably skillful, capable

of creating any illusion of universal harmony, often by depicting places

where mountains meet waters. It is possible that he would favor this setting

because it reminded him of Amoy Island, in South China, where he was born,

but it is also true that this type of setting has almost always been favored

throughout Chinese history. Mountain/water painting was eventually elevated

to an almost canonical form at the time when the concept of literati was

developed. This was to make sure that nature and life are even better

understood as a fusion of complementary elements. The reason being that

water symbolizes fertility or an ability to bring forth life, and mountains

are what water needs to fertilize it or, in other words, to make life

happen.

Chiu will frequently bring to his landscapes another element of traditional

painting, the empty spaces or voids. These voids, taking up large part

of scrolls, are introduced to take us to the hidden – the vital

spirit, but also to bring some sense of hope. They symbolize hope, since

what is painted is the past, with no change, and what is left unpainted

is the future, or change. Chiu employed these empty spaces on his own

terms by working with color, as with his sky, typically painted with whitish

blue with very little variation, sometimes using even half of the canvas.

A good example of his use of voids in a mountain-water composition is

Lake Lure, North Carolina. Here, it is not only the sky but mainly the

lake that is the void, although it is painted in a very soft and light

green.

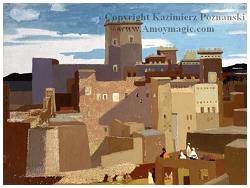

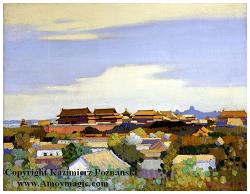

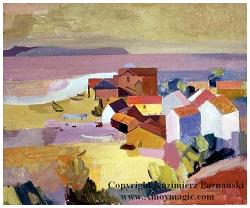

In the literati approach to landscape, people would either be omitted

or given very little space, usually in a corner of the painting and blended

with the background. This is another element that interested Chiu. Figures

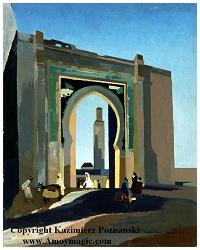

appear most often in his earlier paintings, as in the Moroccan series,

where massive architectural compositions, to be seen as a substitute for

landscape, are occasionally inhabited with small dwellers; as in his piece

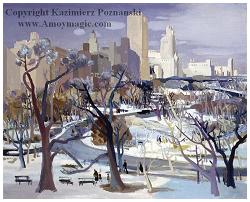

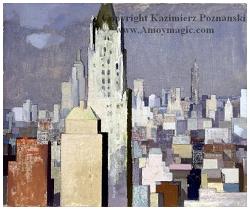

Buildings, Morocco. The same pattern can be found in another series of

urban landscapes by Chiu, namely in his views of New York, where the influence

of his long-time friend and fellow artist Georgia O’Keeffee can

be easily detected. Filled with movement of people and cars, but also

built with stiff walls, South Central Park, New York is a very good illustration

here.

Back to top

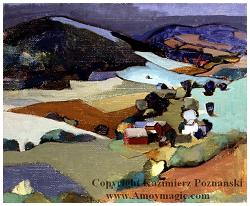

When needing to show distance or depth, Chinese traditional artists resorted

to a simple device, namely, they broke up the flat areas by bringing in

horizontal registers rather than employing Western-type perspective strategies,

with a single focal point. It was a sign of master skills to fit as many

as possible such demarcation lines to gain the best visual effect; another

skill being the ability to play with multiple horizons, separating sky

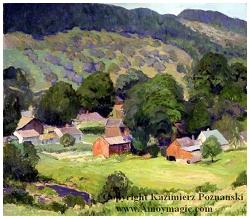

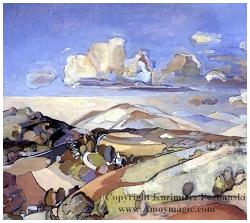

from land, to increase the sense of illusion. One masterful illustration

of Chiu’s approach to constructing a sense of perspective in this

manner is Vermont Landscape. Here, Chiu introduces us to a tranquil and

charming place set within several, at least twenty different combinations

of horizontal registers forming the fields, valleys, and hills.

Regarding the use of light, Chiu generally stays away from using light

to create an impression of depth. Although his canvases are typically

saturated with light, with a sunny aura, his light source is seldom detectable.

This is a practice from the Chinese tradition that is meant to emphasize

the two-dimensionality, with an underlying flatness of the pictured objects.

The extensive use of sinuous lines intensifies this sense of flatness

in Chinese traditional artwork. The artists suggest, rather than describe

their landscapes through linear expressions rather than attending to modeling

the surfaces. Through linear allusions, artists communicate that it is

not the outer that is relevant, but rather what is inside; and in this

way they open an object to the inspection of the spirit .

Back to top

Chiu himself would often design his landscapes, or other scenes, with

the frequent use of fully exposed lyrical lines, as evidenced in his monumental

Central Pownall, Vermont, one of his latest works, and probably the most

prominent in this group. Here, a massive and iconic landscape is organized

through the use of dark lines, which, in fact, are charcoal marks from

the initial sketch executed by the artist. And, in accordance with the

Chinese tradition, he made certain that these exposed lines of black color

are full of life, meaning that they lack precision and tend not to be

finished. Since, as Chinese tradition posits, although equated with being

happy, life is full of imperfection and nothing is ever finished, and

painting, as a tribute to life itself, cannot be different.

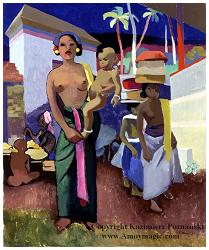

The area where Chiu seemed to depart most from the Chinese tradition is

that, of course, he chose an oil over a water-based medium, but even in

this respect, it is a controlled departure. Trying to keep the Western

technique form interfering with his Chinese meanings, Chiu retained in

his landscape oils very much the quality of a watercolor or ink work of

the scroll artists. Except for many of his early works, most notably those

from Bali, when he painted in the company of two American artists, John

Sitton and Ken Johnston, Chiu stayed away from the heavy application of

paint, instead he used a diluted color and applying thin leyers. In this

way, he was able to gain almost the same sense of softness and transparency

on canvas as a traditional Chinese artist would accomplish on paper.

Back to top

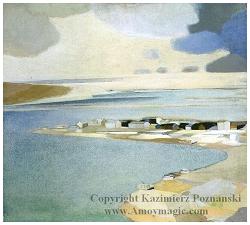

There is hardly a better example of this watery look than Ullapool, Scotland,

one of the few paintings that Chiu took to a number of exhibitions marked

as not available for sale. This is surely one of his best paintings, one

that, despite its relatively early date, also happens to probably contain

more references to the Chinese artistic tradition than the majority of

his other works. It has an unmistakably Chinese mystique, showing a peaceful

and purified landscape with completely balanced space\s, and not surprisingly,

bringing mountains and water together, to show the dependent opposites,

and a sky to represent the nothingness. All of this extremely delicately

executed with a minimum amount of paint in pale shades and subdued colors,

and with only little color contrasts.

The fact that Chiu was extremely innovative, searching constantly for

the most effective execution, is witnessed by the enormous variation in

his work, though he would never lose his very own sense of artistic style.

With this impressive flexibility, seeking inspiration or suggestion from

various sources, he never forgot that, as a Chinese artist, he was to

use his tools primarily to deliver a moral message. This is why he took

us, in his landscapes, to the most pleasurable, calming, and reflective

spaces, which he landscaped with the clear intention of making us realize

how happy places in this world, or nature of ours are. And to tell us,

or whisper to us, how happy we all could be by accepting its rules, those

of a good disposition to other beings – respect and generosity.

Back to top

Bibliography:

Binyon, Laurence. The Spirit of Man in Asian Art. New York: Dover Publications, 1935.

Chaves, Jonathan. The Chinese Painter as Poet. China Institute Gallery, China Institute, New York, 2000.

Holland, Cotter. “In Old China’s Stormiest Times Nature was the Eye.” New York Times, September13, 2002.

Miyagawa, Torao, editor. Chinese Painting. New York: Weatherhill/Tankosha,

1983.

Rowley, George, Principles of Chinese Painting. Princeton University Press,

1959.

Salpeter, Harry. ”The Travels of Teng Chiu.” Esquire, March.1943.

Sickman, Lawrence and Alexander Soper. The Art and Architecture of China. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1968.

Silbergeld, Jerome. Mind Landscape. The Paintings of C.C. Wang. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1989.

Sullivan, Michael, The Arts of China, Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1984

Sze, Mai-Mai, “The Way of Chinese Painting. The Ideas and Technique”,

New York: Vintage Books, 1959

“A good traveler is one who does not know where

he is going to, and a perfect traveler does not know where he came from.”

Lin Yutang

Back to top

TRAVEL

LINKS  Favorite

Fujian Sites

Favorite

Fujian Sites  Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album  Xiamen

Xiamen

Gulangyu

Gulangyu

Fujian

Guides

Fujian

Guides  Quanzhou

Quanzhou

Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

Longyan

Longyan

Wuyi

Mtn

Wuyi

Mtn  Ningde

Ningde

Putian

Putian

Sanming

Sanming

Zhouning

Zhouning

Taimu

Mtn.

Taimu

Mtn.  Roundhouses

Roundhouses

Bridges

Bridges

Jiangxi

Jiangxi

Guilin

Guilin

Order

Books

Order

Books

Readers'

Letters

Readers'

Letters

Last Updated: May 2007

![]()

DAILY

LINKS

![]() FAQs

Questions?

FAQs

Questions?

![]() Real

Estate

Real

Estate

![]() Shopping

Shopping

![]() Maps

Maps

![]() Bookstores

Bookstores

![]() Trains

Trains

![]() Busses

Busses

![]() Car

Rental

Car

Rental

![]() Hotels

Hotels

![]() News

(CT)

News

(CT)

![]() Medical

& Dental

Medical

& Dental

![]() YMCA

Volunteer!

YMCA

Volunteer! ![]()

![]() XICF

Fellowship

XICF

Fellowship

![]() Churches

Churches

![]()

![]()

![]() Temples

Temples![]()

![]() Mosque

Mosque

![]() Expat

Groups

Expat

Groups

![]() Maids

Maids

![]() Phone

#s

Phone

#s

EDUCATION

![]() Xiamen

University

Xiamen

University

![]() XIS(Int'l

School)

XIS(Int'l

School)

![]() Study

Mandarin

Study

Mandarin

![]() CSP(China

Studies)

CSP(China

Studies)

![]() Library

Library

![]() Museums

Museums

![]() History

History

DINING ![]() Tea

Houses

Tea

Houses

![]() Restaurants

Restaurants

![]() Asian

Asian

![]() Veggie

Veggie

![]() Junk

Food

Junk

Food

![]() Chinese

Chinese

![]() Italian

Italian

![]() International

International![]()

![]() Visas

4 aliens

Visas

4 aliens

RECREATION

![]() Massage!

Massage!

![]() Beaches

Beaches

![]() Fly

Kites

Fly

Kites

![]() Sports

Sports

![]() Boardwalk

Boardwalk

![]() Parks

Parks

![]() Pets

Pets

![]() Birdwatching

Birdwatching

![]() Kung

Fu

Kung

Fu ![]() Hiking

Hiking

![]() Music

Events

Music

Events

![]() Cinema

Cinema

![]() Festival&Culture

Festival&Culture

![]() Humor&

Humor&![]() Fun

Fotos

Fun

Fotos![]()

BUSINESS

![]() Doing

Business

Doing

Business

![]() Jobs!(teach/work)

Jobs!(teach/work)

![]() Hire

Workers

Hire

Workers

![]() Foreign

Companies

Foreign

Companies

![]() CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

![]() MTS(Translation)

MTS(Translation)

![]()

Back to Top