![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

AMOY MAGIC SITE from

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access Amoy

Magic Site from

Click

to Access Amoy

Magic Site from

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

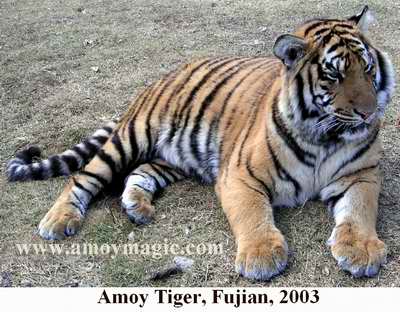

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days

Tibet

in 80 Days![]()

![]() Amoy

Vampires!

Amoy

Vampires!

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

Please

CLICK THUMBNAILS for larger photos

![]() Hills'

P

Hills'

P hoto

Album!

hoto

Album!

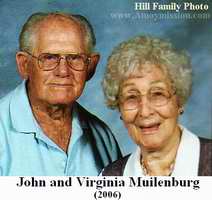

John

& Virginia Muilenberg of Amoy

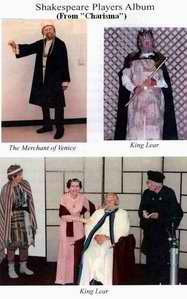

Minister-Missionary-Sailor-Shakespearean!

Intro

Imagine a 69-year-yound man and his

wife taking a few years off to sail a small boat around Europe and across

the Atlantic! That's what John and Virginia did, after a long career

that included 8 years in Amoy (1942-1950),

which included a year of teaching at my own Xiamen University.

Intro

Imagine a 69-year-yound man and his

wife taking a few years off to sail a small boat around Europe and across

the Atlantic! That's what John and Virginia did, after a long career

that included 8 years in Amoy (1942-1950),

which included a year of teaching at my own Xiamen University.

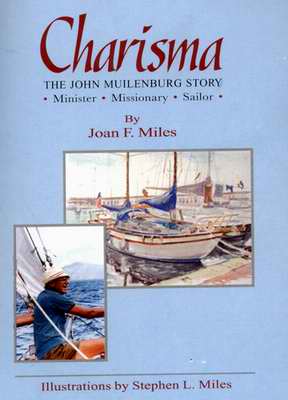

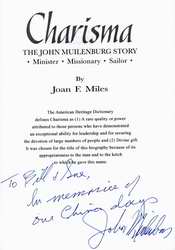

In August, 2007, I was blessed to meet this 96-year-young man at the home of Jack and Joanne Hill in Penney Farms, Florida. In October, 2007, Mr. Muilenberg gave me permission to use an excerpt from his delightful biography, "Charisma--The John Muilenburg Story: Minister, Missionary, Sailor," by Joan F. Miles (with great illustrations by Stephen L. Miles). Buy the book at Amazon.com or visit www.sandjmilesbooks.com or e-mail:joanef@comcast.net Below is chapter four of "Charisma" (copyright 2006 by Joan F. Miles. S&J Miles Publications, 2412 Old Pine Trail, Orange Park, FL 32003)

Missionary

Years in China 1942-1950

Missionary

Years in China 1942-1950

(Chapter 4 of "Charisma", by Joan F. Miles)

In the spring of 1942, the Board of Foreign Missions accepted John; and

in a very meaningful ceremony along with others who had been accepted,

he was made an official missionary to China. The ceremony was held in

the Reformed Church in Albany, New York, a very historic church, which

had been established in 1648 by Dutch people. Following his appointment

and prior to his going to California to study the Chinese language, he

went to Holland, Michigan, to visit his mother, who was now in her late

seventies or early eighties, and other brothers and sisters in the area.

His father had died the previous year. He then took the train to Berkeley,

California.

On the way to California,

John's adventurous spirit emerged. He got off the train at Williams, Arizona,

to explore the Grand Canyon. Because he was young and vigorous, it was

not enough for him to view the canyon from the rim. Instead, he hiked

down into its vast belly, spent a couple of nights in a lodge right on

the Colorado River, and then hiked back up.

When he arrived in Berkeley, he entered the Chinese Language School at the University of California. This school had been transferred from Peking where it had been in existence for many years. John claims that it was a good well-run school. Here he began his very intense study of the Mandarin language, the official language of China, and of the Chinese culture and history. On the assumption that he would spend the rest of his life in China, he felt it was important to learn this language, even though he knew that the people where he would be sent would probably speak a dialect. It was a very exciting time for him because the experience was pertinent to the life he expected to live in China. He stayed in the International House on the University of California campus where many, many students from different nations were also housed. Because his roommate was Chinese, he was able to practice what he had learned each day. John recalls that his roommate was a little bit bored with this, but he was very cooperative nonetheless.

John spent four or

five hours in class every day with ve ry

fine Chinese instructors who had come from China to serve as teachers.

Although he found the study of Mandarin Chinese a very challenging time

for him, he did take timeout to visit and get acquainted for the first

time with one of his older half-sisters who lived in Berkeley.

ry

fine Chinese instructors who had come from China to serve as teachers.

Although he found the study of Mandarin Chinese a very challenging time

for him, he did take timeout to visit and get acquainted for the first

time with one of his older half-sisters who lived in Berkeley.

Of course, the fact that there were some very attractive young women in the school served as some distraction to John, and he admits that he was involved to a degree with some of them. However, it was his involvement in the Presbyterian Church in Berkeley, where he was teaching Sunday School and singing in the choir, that was to introduce him to the love of his life, Virginia.

That his and her

versions of their meeting differ some what should come as no surprise

to married couples or to those who are fortunate to know both John and

Virginia. He says that he was sitting at the piano one Sunday morning,

playing and practicing his singing, when Virginia came up behind him and

asked if he would like her to sing along with him. She says she  asked

him if he would like to have an audience to which he replied, "Not

especially!" How ever it happened, their lives became intertwined

at that moment: and from this point, his story becomes hers aswell.

asked

him if he would like to have an audience to which he replied, "Not

especially!" How ever it happened, their lives became intertwined

at that moment: and from this point, his story becomes hers aswell.

Virginia was a graduate of the University of California and a high school

English teacher in the neighboring town of Piedmont. She, too, came from

a strong religious background; so having much in common, they began a

serious relationship. She was aware that John was going to China to be

a missionary but was not turned off by this, as many a young woman would

have been. She felt that it would be a wonderful fulfillment of her own

life. Three months following their meeting in what John calls "a

ridiculously short time," they were engaged and then married on April

2,1944 in the First Presbyterian Church in Berkeley. "However short

was this courtship," John exclaims, "it worked! We are still

together 60 years later." John then moved into Virginia's apartment

and continued his course of studies while she finished out her teaching

contract.

In

the spring of 1944, John finished two years of concentrated study. It

had taken him this length of time with his self-confessed "limited

resources" to absorb all there was to learn. He could now speak,

read, and write in the Chinese language in what he calls "a very

limited way" and had even begun to prepare sermons in Chinese. It

is safe to say at this point that his analysis of his academic ability

seems somewhat understated.

In

the spring of 1944, John finished two years of concentrated study. It

had taken him this length of time with his self-confessed "limited

resources" to absorb all there was to learn. He could now speak,

read, and write in the Chinese language in what he calls "a very

limited way" and had even begun to prepare sermons in Chinese. It

is safe to say at this point that his analysis of his academic ability

seems somewhat understated.

In the summer of that year, John was assigned to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, to take a special course in basic agricultural and farming methods. It was developed for missionaries who were going to China to prepare for service in a rural setting. It was not a course he would have chosen but, as the ongoing war was preventing his going to China, it did seem the best thing. John remembers one very important and most significant experience he had while he was at Cornell. A world famous missionary named Laubach, who had developed what was called the one-on-one method of teaching literacy and was well known in government circles, was teaching there. In the course of one of his lectures, he told of hearing about a top secret bomb of untold power that was being developed. It was not until the bomb fell on Hiroshima that John realized what he had been talking about.

John and Virginia lived in Ithaca from the fall of 1944 until the summer of 1945. The winter during this period of time was brutal. John recalls that not one day in the month of October did the sun shine. Virginia had no experience with winter. She had been born in Mississippi but had lived most of her life in Westminster, a town in southern California, where her father, after encountering a number of disasters as a farmer in Mississippi, had moved the family to go to work in the oil fields. John's and Virginia's little house was in the town, but the campus was way up on top of a hill. Every day they had to trudge up that hill to class. One morning this became just too much for Virginia. In the midst of a howling blizzard, as John describes it, she dragged herself uphill, bitterly ruing the day she ever decided to follow him. However, somehow they managed to survive that brutal winter and on July 21, 1945 in Ithaca, New York, their first-born son Peter came into the world.

That same winter Hitler made his last ditch effort to break the Allies by launching a huge onslaught in the dead of winter for which the allies were not fully prepared. The Germans at first were very successful but were finally stopped during a counter offensive known as the Battle of the Bulge in which American troops suffered horrendous losses as hundreds of young men in their late teens lost their lives. John remembers suffering excruciating pain as he agonized over this.

Peace finally came to Europe in the spring of 1945 and it began to look as if John and other missionaries might at last be able to go to China. However, as it was still chaotic in the Pacific, they were moved from Ithaca to New York City to gain some experience in the interim. John was assigned to work in the office of the Reformed Church and he remained there for about six months "trying to be useful." Although Japan had surrendered in the summer of 1945, it was not until the spring of 1946 that they got the word. It was now possible for the missionaries to depart for China.

John and Virginia set out with baby Peter to drive across the country, stopping to see friends along the way. When they arrived in California, they were informed that women and children could not yet go to China with their husbands. John, although he found it most difficult to leave Virginia and their small son, decided he should go and prepare the way for their arrival whenever they were given the green light. So, in April of 1946, he boarded a freighter bound for Shanghai, which made its way from Houston through the Panama Canal, and on to China. One of the missionaries on board was a seasoned missionary in China who regaled John with stories of his experiences there and helped him practice his rudimentary Chinese. They landed in Shanghai in May, and what an unforgettable and exciting scene it was on that wharf! Hundreds of Chinese coolies were milling about, either carrying burdens or pulling rickshaws, while all kinds of trucks maneuvered among them. John reports that the confusion was so enormous it made him wonder what he was getting himself into.

However, after a few days in Shanghai, he was put on a freighter, which proceeded down the coast for about 500 miles into the port of Amoy, one of the major Chinese ports. There, several older missionaries met him. John was impressed with its beautiful harbor but not with the fact that the Amoy dialect was totally different from the Mandarin dialect. "A Mandarin-speaking Chinese can understand practically nothing an Amoy-speaking Chinese is saying," exclaims John. This was a huge headache for him because it meant that he had to begin his language study all over again, necessitated by the fact that there was very little English spoken in China in those days. John was assigned to live in one of the mission houses in Amoy with several of the older missionaries whose job was to whip the younger missionaries into shape, to teach them the many things they had learned over their years in China, and to introduce them to life in a church there. They also had a tough old Chinese teacher for their language study. John claims it was a very valuable experience for him because he learned from them the many things he needed to know about the church in China in order to be effective in his work there. The Reformed Church had been one of the first of the American denominations to send missionaries to China. The very first missionary to get to China was an Englishman named Robert Morrison who arrived in Canton in 1830. However, the first missionary from the Reformed Church was a man named David Abeel. This was important to know, according to John, because when John arrived the church in China had already been there for over one hundred years. As he explains, a more accurate term than missionary for his assignment would be "a fraternal worker." His role was not that of establishing a church as the early missionaries had done because there were already seminaries, schools, and hospitals as well as churches there. Thus, his role was to help the Chinese and to work with the missionaries already there as a fraternal worker.

John was in China

without his wife and small child from April, 1946 until Christmas time

when a boatload of women and children bound for China, Japan, and India

arrived in Hong Kong and with them, Virginia and Peter. John was there

to meet them, and what a joyful reunion it was with Virginia and how good

it was to see his little boy after so many months! Virginia had had a

rough time in this interim away from John. Peter had cried a lot and his

constant crying had made the place where she had hoped to stay untenable;

so she had been forced to move in with her brother and sister-in-law up

in the mountains of California. It worked out all right, but still it

was difficult living in someone else's house. So she was delighted to

get to China and to be with John at long last.

While in Hong Kong, John witnessed what he called one of the funniest

scenes of his life. As he describes it, one of the missionary ladies who

was coming back to Amoy, an extremely heavy

woman, a "Mrs. Five-by-Five," got into a rickshaw. As the rickshaw

man started off unaware of the weight he was carrying, somehow her weight

shifted. This caused the rickshaw to rear back, catapulting the rickshaw

man into the air, holding onto the handles of the rickshaw, frantically

kicking his feet, and depositing the missionary lady on the pavement.

To this day, John can not tell this story without laughing his way through

the telling of it.

Returning from Hong Kong to Amoy, John and Virginia with their little boy Peter set up housekeeping and were assigned a cook and a servant. There, John was to continue his study of Chinese along with the other missionaries as learning to speak Amoy takes a couple of years. Language study became a part of Virginia's daily life as well. Not only did they need to communicate with their new friends at church and at the University, but also Virginia had to deal with the male cook who had been assigned to them. He spoke no English and Virginia very little Amoy dialect so the daily planning session was a real strain on both of them. These sessions with the cook and his wife who cleaned and did the laundry "by hand!" as Virginia exclaims, was a strong incentive for her to learn the dialect as fast as possible. Another incentive was the requirement of the Board of Missions that they pass language exams in which they were required to recognize and write 1000 Chinese characters in addition to being able to converse at an elementary level. "Chinese, being a tonal language, and the Amoy dialect having seven different tones afforded many a hilarious moment," adds Virginia, "due to our using the wrong tone for a given character and eliciting inevitable smiles and laughter from our audience. Just imagine our saying we took a snake out of our pocket instead of money!"

They lived quite happily in a missionary compound in Amoy for about six months before they were assigned to a little town called Tung An, about 40 miles inland from Amoy. There was no language school for them there; just a couple of Chinese schoolteachers from the local school for Chinese students. However, they were faithful and took their teaching seriously so that John and Virginia managed to pass their first-year exam and began to get the feel of the language with a minimum of wrong tones.

The missionaries

assigned to Tung An were also to begin work in

the church and to move about the countryside and talk to people in order

to become true fraternal workers. They were to act as assistants of the

pastor of the church in this little town, to bring fresh ideas and fresh

personalities into play as they moved about the countryside, but they

were not there to run the show. That was the pastor's responsibility.

Sometimes John made evangelizing trips into the mountains to preach and

show slides to Chinese who had never heard the Gospel and, in some cases,

had never seen a white man. The Chinese he worked among were simple peasants,

owning little of material value. Often shipments of clothing and other

goods would come in to be distributed among the people.

John tells an amusing story about one man who found in one such shipment

a union suit, sometimes referred to as long-Johns, that fit him just perfectly.

So happy was he with this prized possession that he appeared at church

on the following Sunday where he was assigned to take up the collection

proudly wearing his union suit.

Soon after they arrived in Tung An, the Muilenburgs witnessed a ritual they were to learn was a typical Buddhist celebration called the "Great Heavenly Grandfather Birthday." It went on for several days and they had no idea what it was all about. Outside the makeshift temple were hung two enormous skinned pigs on each side of the small doors, probably John thought, for roasting later on. There was much singing and banging of drums going on right behind their house. In spite of the fact that they didn't understand exactly what was going on, this ritual did introduce them to one of the indigenous rituals and taught them something about the Chinese culture.

In Tung

An, John and Virginia lived on the edge of some mountains. In these

mountains lived many tigers; and sometimes

these tigers would come down into the village, especially in the dry season,

to forage for food. Therein lies one of the most horrendous and appalling

experiences they were to endure. There was a hospital

in the village which was staffed by a single doctor and one nurse.

As it was the only hospital for the people in the whole area, the custom

of the time was that the family of a patient there would send a member

of the family to assist the nurse in his or her care. In keeping with

this custom, the family of an old man in this hospital had sent a grandchild,

a little girl only eight years old, to help in his care by cooking his

rice on an outside fire and by performing other simple duties.

One day, after having cooked his rice, she was outside on some rocks washing

his dishes, when suddenly a huge tiger leapt

out of the forest, scaled a five-foot wall, snapped this little child

up in his jaws, and dragged her off into the mountains where he devoured

her. [Read about the Tennessee Caldwell family--famous Amoy

Tiger hunters!]

The whole village

was horrified as well as terrified, the Muilenburgs included! After all,

they had their small son Peter to be concerned about. John and the doctor

in the hospital contacted the police and were told they could go up into

the mountains and try to find the remains of the child but that "they

had better take this gun." Armed with the gun given them by the police,

John and the doctor set out to try to trace this animal. Along the trail,

they came upon bits of the child's clothing as well as bits of the remains

of the child but not the tiger. Back at police

headquarters, John was told, "You had better keep the gun in case

this animal comes back." And so John was left with the gun and an

elusive man-eating tiger that could return

to the village at any time.

Soon after this, their cook, who lived in a little house behind their

house, came running to them with a terrified look on his face, screaming,

"Come out into the yard!" There John and Virginia saw the tracks

of a huge tiger and they were just as terrified

as the Chinese cook. Outside their house they had an electric generator;

and every night, if they wanted to listen to music or turn on the lights,

John had to go out and start it. He remembers that he was actually afraid

to do it. So Virginia would stand on the porch banging on a pot to scare

the tiger away while he did it. When he and the other missionaries had

to go out at night, either to each other's houses or to church or wherever,

they would take pans to bang on as they walked. They had no other means

of transportation except by foot and, as John expressed it, "It was

downright dangerous with that tiger lurking about and we were scared."

Finally, one night John and the other missionaries got a goat and staked

it in the middle of the compound while John sat up on his balcony all

night long with the gun. The police had given them permission to do this

but, as John puts it, "Those animals were too smart. I never got

a shot!"

Here in Tung

An, their little boy Peter grew up playing with their cook's little

boy, who was about the same age as Peter, and his two lovely daughters,

who were older. They played a game called Bo yan gin and Peter learned

Chinese. "It was his first language practically," says John

with a chuckle, "and it was funny how that kid could rattle off Chinese

within the context of his playing with them."

!

After John and his family had been in Tung An

about a year and a half, John was reassigned to Amoy

to live and to begin his work with Chinese students. There was a national

university [Xiamen University] there with hundreds

of students, many of whom gathered frequently to read, relax, and have

soft drinks in a Commons Building, which had been erected by the YMCA

on the campus of the university. It was a Christian

operation and it was there that John was assigned to begin to establish

his relationship with the students.

This occurred during the days of the Communist uprising in China. The Communist regime under Mao Tse Tung was having great success in its war against the Chinese Nationalists, as Chang Kai Shek's forces had been weakened during the Sino-Japanese war. According to John, many of the students had been greatly affected by the Communist propaganda, by Communist teaching, and many of them at heart were sympathetic to the Communist movement. This was understandable because the people had little to look forward to under the Nationalists. The Communists made it appear that they were interested mainly in changing the economic structure of China, but basically they wanted to appropriate land from the rich landowners and give it to the poor. While this was attractive to the students, many of them were also very open to the Gospel and so entered into all kinds of wonderful meetings with the missionaries in programs of study and recreation. Yet it was a very dangerous time for them because the Nationalist regime was bent on stamping out any kind of sympathy for Communism on the college campuses and on arresting any who in any open way espoused Communism. Indeed, one day the Nationalists came and arrested a number of John's students, took them away, and shot and killed them, much to John's horror, as well as to the rest of the missionaries, even though they knew the Nationalists did this because they were fighting for their lives. Mao Tse Tung and his forces were taking over the country, and Chang Kai Shek, with his forces fighting a losing battle, felt the Nationalists were forced to use such extreme measures.

"We missionaries," says John, "obviously stayed out of it. Some of us were somewhat sympathetic to agrarian reform, but we kept insisting that we were not political." This was difficult for them because they saw the poverty. It was unbelievable. The economy was absolutely drowning in it. The currency was worthless. It got so bad that John and Virginia's cook would have to take a suitcase full of Chinese money to go shopping for food. It took one million of the Chinese currency to equal one American dollar. The economic condition of the country was abysmal. Even in the town of Amoy it was common to see a person lying on the street, dying of hunger or disease. John and the rest of the missionaries saw this and they were conflicted; it wasn't that some of them were in favor of the political idea of Communism, but they were acutely aware of the severity of the conditions, and their hearts bled for the people.

It was a very trying time. The country was in turmoil economically, politically, socially, and it was obvious that the Chinese were in trouble. The missionaries were in turmoil as to whether they should stay and see how the whole thing played out or leave. To make it doubly difficult for the Muilenburgs, during this time their second son was born; so now they had two small children. Did they jeopardize their lives by staying? It became an important question for them. Who knew what was going to happen?

At length John and

Virginia decided that they had committed their lives to China, so they

would stick it out and stay on at the University,

come what may.

They named their second son Jonathan. He was born in the local mission

hospital where he made his way into this world in darkness and by the

aid of flashlights. While he was in process of being born, all the hospital

lights went out. "Since this was the son who later became the rebellious

one," says John, with his unique brand of humor, "I don't know

whether that had a bearing on his future or not!"

During this time, John and Virginia had students coming into their house all the time, sometimes as many as 40 or more. The Muilenburgs had very good recording facilities and an excellent collection of music, so music sessions were well attended, as were the Bible study sessions. In addition to this aspect of their lives, John was invited by the University Head to share his knowledge of history with the students, history having been his major in college. He had to do this in English because the language at the University was Mandarin and, as he had spent all his time there learning Amoy, his Mandarin was rusty. Thankfully, this did not prove to be a problem because a lot of the students had majored in English, and so they understood it.

Now begins an incredible adventure for John. As the Communists were now moving inexorably south from Peking to Shanghai, and heading down the coast to Fuchow, which was only about 300 miles north of Amoy, the missionaries who had decided to stay in China knew it was obviously only a matter of time before their town would be attacked, and they realized that certain medicines needed for their children and their own lives would not be available. So they asked John to take a quick trip to Hong Kong to buy up all the supplies and vitamins and special foods he could. That they chose John speaks eloquently of the respect his fellow missionaries must have had for his resourcefulness.

Because John couldn't get a plane, he took a ship and, after three days, arrived in Hong Kong. There he received a message that the Communist army had made a surprise push and were within the environs of Amoy, preparing to surround the town. So John knew that time was of the essence if he were to get back, as it would become increasingly dangerous for boats in the area. He hastened to do his shopping and managed to obtain a big load of medicines and food supplies to take back to Amoy. He then went to buy a ticket for his return trip only to be told there was no way to return by boat.

John had heard about the Flying Tigers flying behind enemy lines to take out people who wanted to leave and figured that they would be willing to fly him in. So he went to the office of the Flying Tigers only to be told, "NO WAY!" The airport in Amoy had been surrounded even though the Communists had not yet taken Amoy itself. John thought, "My goodness, what do I do now? I have to get back to my wife and kids!" He decided to fly to Taiwan, which was 90 miles across the Straits of Taiwan. He didn't have a visa for Taiwan and the woman who sold the tickets for the flight advised him that, if he didn't have a visa, the authorities might send him right back. John decided to take that chance as his options were fast disappearing. He bought a ticket knowing that somehow he would have to bluff his way through customs and get by the immigration officials. So with trepidation, his heart pounding against his chest wall, John walked through customs silently uttering a little prayer, when to his utter astonishment, the immigration official took one look at him and said, "Off you go!"

Whereupon John breathed

a deep sigh of relief, thanking God for his intervention. He then went

to the Canadian Presbyterian mission office in Taipei and told his story.

He informed them that he had to borrow $1000 to charter a plane and was

told that they could only come up with $500. John said, "I'll take

it!" and rushed over to the office of the Flying Tigers in Taipei.

He told the girl behind the counter that he had to get back to Amoy,

that his family was there, and that he had "all this stuff"

for their and others' survival. The girl merely sighed resignedly and

offered lamely that she didn't know how that was possible. Just as John

was approaching his wit's end, he heard from behind the counter a voice

with clearly an American southern accent say, "I'll fly you in."

Because John couldn't see who was speaking, he could only wonder who this

man was. To his utter surprise, out from behind the counter emerged this

black man who carried the name of Wong and who said, "It'll cost

you 500 bucks!" To this, John replied, "You've got a deal!"

As it turned out this man's father was a Chinese laundry man in Atlanta

named Wong and his mother an African-American, and that's how he became

Charlie Wong. Charlie Wong told John to meet him at the airport on the

following morning at 6:30 a.m. and warned him that they might have trouble

getting off because he was not supposed to fly out according to an edict

by the Nationalists. However, if John would meet him at the corner of

the airport he specified, he thought they could get off. So John met him

there on the following morning, and he and Charlie Wong took off in a

single engine Piper Cub and flew over the straits. John remembers that

it was a beautiful morning. The sun was shining brightly, the sky was

a clear blue, and John was beginning to relax. Perhaps he was going to

make it back after all. As they approached the airport in Amoy,

however, John saw the puffs of mortar shells and thought to himself with

a sinking feeling that Charlie Wong would never dare land when shelling

was going on. His thoughts were interrupted when he heard Wong say, "Never

mind the shelling, just do what I tell you. When I tell you to throw out

your bags, you throw them out. I can't afford to stop but I will slow

down as much as I can without stalling and when I say jump, you jump!"

Since he had no other choice, John did as he was told. When Charlie Wong

opened the door and said, "Out you go!"¡ª out went John, making

himself into as much of a ball as he could. He landed, rolled over a few

times, and by the time he looked up, the plane was already up in the sky

heading back to Taiwan with Charley Wong having John's 500 bucks in hand,

which John says he did not begrudge him.

As John lay on the ground trying to pull himself together, the next thing

he knew three soldiers carrying guns came running toward him. They said,

"Who are you coming down out of the sky when everyone else is leaving?"

John knew that all the rich Chinese were leaving and anybody who had any means whatever was getting out of China. He knew, too, that these were Nationalist soldiers so he said, "I want to be here with you when you face the Communists!"

That went over big with them; so they took him into the airport, gave him a phone, and he called Virginia. How good it was for him to hear her voice and for her to hear his! Shortly thereafter, John crossed over the water from the Amoy airport in a water taxi and arrived home to a very joyous homecoming. Later, in prayer, he thanked the Lord for carrying him all the way and allowing him to get back safely to Virginia and his family.

The Nationalist soldiers, having been driven by Mao Tse Tung and his army all the way from the north of China down to Amoy and to Kolangsu where the Muilenburgs now lived, as Virginia put it, were now a sad lot: ragged, hungry, many of them carrying umbrellas instead of guns. However, they did manage to escape by confiscating small boats called sampans from the local fishermen and making their way back to Taiwan. Every night the Muilenburgs had to endure shells screaming over them as the Communists continued to shell Amoy, and their little island was in the path.

Fortunately, sometime prior to this, they had realized that they were going to be in this dangerous situation as their house on a hilltop was very much exposed. It had been built on a level area dug out of the mountainside. So, with the help of their Chinese friends, all those living there at the time built a bomb shelter by digging straight into the hillside and then making a left angle turn to protect themselves should a bomb land in the entry way. At the time the Muilenburgs had a big dog that went absolutely berserk as the shelling continued night after night. Not wanting to put him outside, they finally shut him up in a dark closet so he couldn't see anything and hopefully the sound would be muffled.

After enduring five nights of constant shelling, they awoke one morning to see communist soldiers with the red star on their hats climbing up the hill toward them. John confides that they were very well disciplined, didn't bother them, and even refused the cigarettes that he went out to offer them. They had reached the island by inflating hundreds of truck inner tubes and getting into them and floating over while holding their guns over their heads. Obviously impressed with their ingenuity, John says, "Imagine that! Using inner tubes, they attacked our island!"

The Red Army dug in, taking over the local police and government offices, and so began a difficult period under Communist rule. The Korean War was now at its height. American soldiers were fighting Korean soldiers and President Truman had sent the 7th Fleet to create a blockade between Taiwan and Mainland China. This infuriated the Communists who had every intention of attacking Taiwan because that was where Chang Kai Shek was now holed up. Says John, "From our house on top of the hill we could see many Chinese junks under diesel power practicing maneuvers in preparation for this attack; but Truman's blockade frustrated this, and so to this day Taiwan is still independent."

Those missionaries who had stayed felt that they would be able to continue as they had in the past, attending church services and continuing with their aid as fraternal workers. Also, John had every intention of continuing his work at Amoy University; but all of this came to a very sudden halt. "They were," as John puts it, "now clearly identified as enemies of the regime." They had stayed there because they wanted to show solidarity with their Chinese friends, but now they found it even unwise to go to church. The sad fact was that anybody who showed any friendship toward the missionaries was immediately suspect and in danger of his life. It was such an unpleasant atmosphere that even if they ventured out into the streets, they would be subject to insults and to pelting by stones thrown by little kids running behind them. It was almost as if they were under house arrest. They were the enemy. American soldiers were shooting at Chinese soldiers.

Explains John, "The next ten months were very frustrating, to say the least. We couldn't function. Although we were not officially enemies as we had not declared war on China or the Chinese, we found ourselves locked in a very unpleasant situation. In many areas, we who had decided to stay found it impossible to continue our work. Even worse, several of the missionaries in other areas of China were arrested and put on trial. Some actually lost their lives. In light of the restrictions placed on our activities, we spent most of our time confined to our homes. Fortunately, we had many books on hand, and I recall reading some of the greatest books of my life at this time: Tolstoy's War and Peace, Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment, and The Brothers Karamazov."

As if the Communist shelling had not been bad enough, soon after they had taken over Amoy, the Nationalist Army, which was only 90 miles away and had a very sophisticated air force, began sending bombing missions over Amoy; and so the Muilenburgs faced an even greater danger. John remembers one day, while standing on his porch, seeing one of these planes come in very low, followed by the red flash of the bomb exploding as well as the strafing sent up by the Communists, and how glad he was that they had their bomb shelter.

Yet they were not to escape a most frightening experience. One morning as they were having breakfast, suddenly there was a tremendous blast. A bomb, dropping no more than 100 feet from their house, blew out the glass in every window of their home, and the ceiling over their heads started to crumble and then crashed down on the table where they were sitting and into the pancake batter. They had just gotten their children out of the bedroom when this happened; and, had they not done that, they might have been seriously injured as glass shattered all over Peter's bed and Jonathan's crib.

Following that frightful event, whenever they heard planes, they corralled their two children post haste and took refuge in the air raid shelter they had dug into the hillside. The experience so traumatized their son Peter, then five years old, that for many weeks thereafter, even after they had left China, whenever he heard an airplane, he would scream and run for protection. As for John and Virginia, it forced them to decide that, given the danger to their lives and their children's lives, there was no point in staying any longer. So they applied to the authorities in Amoy to leave China.

While they were waiting for permission to leave, a well-educated woman who had studied in a missionary school in Peking as well as at the Sorbonne in France came to visit them in their home. To John's utter astonishment, she revealed that she was now actually a Communist leader and the head of the government in Amoy, and she had come to try to persuade them to stay.

She said, "Why do you want to leave? Don't you realize that we, the Communists, are the wave of the future? Don't you want to ride that wave? Join us in our determination to change the world for the masses of the people. We have work for you. You can go back to Amoy University and become a Professor of World and American History and a teacher of English because we must now learn English because it is the world language."

John and Virginia listened politely but in the end were not persuaded. The danger to which staying exposed their two boys and the fact that Virginia was now expecting their third child made the difference. They had no intention of changing their minds, so they were given permission to leave.

At this time the Communists were importing diesel engines and diesel fuel from Hong Kong and outfitting hundreds of Chinese junks, still planning to make that amphibious assault on Taiwan where Chang Kai Shek and his Nationalist army had fled. The Muilenburgs' plan was to leave via one of the freighters that were bringing in the diesel on its return trip to Hong Kong. Much of what they had collected¡ªcarvings, scrolls, pictures, pieces of chinaware, and the like¡ªthey had to leave behind because the Chinese felt such things were part of their national heritage. So they put together what they could and one night boarded a freighter which left Amoy at midnight. Because they had to get past the Nationalist outposts that would shell any boat they could see, they were allowed no lights. Thus, it was a lightless passage in the dark of night before they reached international waters where they were safe from attack. In due course, they found themselves in Hong Kong, as John says with a sigh of understandable relief, "All four of us!"

There, they were given a place to stay while they awaited a ship to take them back to America and finally were booked on The President Wilson, along with many hundreds of missionaries and others who were making their way back to America. It was a joyful return home after what John describes in his humble way as "a rather eventful Chinese experience."

Here, in his own words, are some of his reflections concerning that experience: "When I could no longer conduct religious services with Chinese students under the Communist regime but still wanted to keep my contact with them, I began attending classes with 50 to 70 Chinese students in a study called The Little Red Book. This was a textbook that Mao Tse Tung had prepared for indoctrination of the masses, and everybody in China in those days who could read had their own Little Red Book. I had my own copy and for several months, I attended classes with these students studying Mao's writings. Many of the 19th century missionaries, who had gone into China in the last 100 to 150 years, in addition to preaching the Gospel, preached the superiority of Western culture, Western education, and Western medicine. By their attitude it was implied that everything that was Western was good and most other things that were Chinese were inferior. This was when the West was going strong and countries like China were considered just backwater. So the West exploited the Chinese. Mao Tse Tung brought this to a grinding halt. He's done a lot for China, but you know many missionary old-timers worried about what was going to happen to all their beautiful churches¡ª 'We come here, we set them up, we organize them, we run them, now what's going to happen?' The truth is that the church in China has expanded beyond all belief under Chinese leadership. There are millions of Chinese Christians now and churches that are able to hold several thousand people. If you don't get to church ahead of time, you don't get a seat. When Billy Graham was there a couple of years ago, he preached to thousands in a football stadium. They say there is a new church being built in China every four or five days. They're small churches, not like our large ones, but there are people worshipping in them. So the church in China is going strong, and that warms my heart!"

Throughout his experience as a missionary in China, John's compassion for the people grew in direct proportion to the suffering he saw them endure as a result of the war going on between the ideological factions represented by Chang Kai Shek on the one hand and Mao Tse Tung on the other. While he could not in all conscience embrace Communism, he was acutely aware of the fact that there was little the common man in China had to look forward to under the Nationalist regime. He felt deeply for the plight of the Chinese students with whom he worked and found his greatest joy in sharing with them his faith and leading some of them to Christ.

Once back in America, the Muilenburgs went to stay at first with Virginia's parents in a little town called Avenal in the San Joaquin Valley where Virginia's father was still working for Standard Oil. It was there that their third child was born. John and Virginia named him Stephen. It was now 1950 and John spent a lot of his time in the next two years visiting churches in the area, telling them about his work in China and what was happening there in relation to Christianity. He also did deputation and other work for the Reformed Church in America.

Enduring and colorful threads weave their way into the tapestry shaping John during this period in his life. First and foremost was the entrance of Virginia into his life, for her influence is to weave strong, golden, and enduring threads in this tapestry for the balance of their lives together. To this thread was added another, the introduction of fatherhood into his life with the births of his first son Peter, second son Jonathan, and third son Stephen, a thread which was to become of significant influence in future decision-making. Other threads introduced to the weave were the discipline he applied to learning the Chinese language, the courage and daring he brought to the obstacles the war between the Communists and Nationalists threw in his path, and the compassion for and loyalty he displayed throughout to the Chinese people he was called to serve. The joy that filled his heart and soul in sharing his faith with so many Chinese students and in leading some to Christ, and his unwavering commitment to and reliance on his faith, and to the peace and justice it seeks for all people were threads completing the weave.

Please Help the "The Amoy Mission Project!" Please share any relevant biographical material and photos for the website and upcoming book, or consider helping with the costs of the site and research materials. All text and photos will remain your property, and photos will be imprinted to prevent unauthorized use.E-mail: amoybill@gmail.com

Snail Mail: Dr. William Brown

Box 1288 Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian PRC 361005

TRAVEL

LINKS  Favorite

Fujian Sites

Favorite

Fujian Sites  Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album  Xiamen

Xiamen

Gulangyu

Gulangyu

Fujian

Guides

Fujian

Guides  Quanzhou

Quanzhou

Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

Longyan

Longyan

Wuyi

Mtn

Wuyi

Mtn  Ningde

Ningde

Putian

Putian

Sanming

Sanming

Zhouning

Zhouning

Taimu

Mtn.

Taimu

Mtn.  Roundhouses

Roundhouses

Bridges

Bridges

Jiangxi

Jiangxi

Guilin

Guilin

Order

Books

Order

Books Readers'

Letters New: Amoy

Vampires! Google

Search

Readers'

Letters New: Amoy

Vampires! Google

Search

Last Updated: October 2007

AMOY

MISSION LINKS

![]()

![]() A.M.

Main Menu

A.M.

Main Menu

![]() RCA

Miss'ry List

RCA

Miss'ry List

![]() AmoyMission-1877

AmoyMission-1877

![]() AmoyMission-1893

AmoyMission-1893

![]() Abeel,

David

Abeel,

David

![]() Beltman

Beltman

![]() Boot

Family

Boot

Family

![]() Broekema,

Ruth

Broekema,

Ruth

![]() Bruce,

Elizabeth

Bruce,

Elizabeth

![]() Burns,

Wm.

Burns,

Wm.

![]() Caldwells

Caldwells

![]() DePree

DePree

![]() Develder,

Wally

Develder,

Wally

![]() Wally's

Memoirs!

Wally's

Memoirs!

![]() Douglas,

Carstairs

Douglas,

Carstairs

![]() Doty,

Elihu

Doty,

Elihu

![]() Duryea,

Wm. Rankin

Duryea,

Wm. Rankin

![]() Esther,Joe

& Marion

Esther,Joe

& Marion

![]() Green,

Katherine

Green,

Katherine

![]() Gutzlaff,

Karl

Gutzlaff,

Karl

![]() Hills,Jack

& Joann

Hills,Jack

& Joann

. ![]() Hill's

Photos.80+

Hill's

Photos.80+

..![]() Keith

H.

Keith

H.![]() Homeschool

Homeschool

![]() Hofstras

Hofstras

![]() Holkeboer,

Tena

Holkeboer,

Tena

![]() Holleman,

M.D.

Holleman,

M.D.

![]() Hope

Hospital

Hope

Hospital

![]() Johnston

Bio

Johnston

Bio

![]() Joralmans

Joralmans

![]() Karsen,

W&R

Karsen,

W&R

![]() Koeppes,

Edwin&Eliz.

Koeppes,

Edwin&Eliz.

![]() Kip,

Leonard W.

Kip,

Leonard W.

![]() Meer

Wm. Vander

Meer

Wm. Vander

![]() Morrison,

Margaret

Morrison,

Margaret

![]() Muilenbergs

Muilenbergs

![]() Neinhuis,

Jean

Neinhuis,

Jean

![]() Oltman,

M.D.

Oltman,

M.D.

![]() Ostrum,

Alvin

Ostrum,

Alvin

![]() Otte,M.D.

Otte,M.D.![]() Last

Days

Last

Days

![]() Platz,

Jessie

Platz,

Jessie

![]() Pohlman,

W. J.

Pohlman,

W. J.

![]() Poppen,

H.& D.

Poppen,

H.& D.

![]() Rapalje,

Daniel

Rapalje,

Daniel

![]() Renskers

Renskers

![]() Talmage,

J.V.N.

Talmage,

J.V.N.

![]() Talman,

Dr.

Talman,

Dr.

![]() Veenschotens

Veenschotens

. ![]() Henry

V.

Henry

V.![]() Stella

V.

Stella

V.

. ![]() Girard

V.

Girard

V.

![]() Veldman,

J.

Veldman,

J.

![]() Voskuil,

H & M

Voskuil,

H & M

![]() Walvoord

Walvoord

![]() Warnshuis,

A.L.

Warnshuis,

A.L.

![]() Zwemer,

Nellie

Zwemer,

Nellie

![]() Fuh-chau

Cemetery

Fuh-chau

Cemetery

![]() City

of Springs

City

of Springs

(Quanzhou, 1902!!)

![]() XM

Churches

XM

Churches ![]()

![]() Church

History

Church

History ![]()

![]() Opium

Wars

Opium

Wars

![]() A.M.

Bibliography

A.M.

Bibliography

![]() YMCA

Volunteer!

YMCA

Volunteer!

![]() XICF

Fellowship

XICF

Fellowship![]()

![]() Temples

Temples![]()

![]() Mosques

Mosques

![]() Christ

in Chinese

Christ

in Chinese

Artists'

Eyes

DAILY LINKS

![]() FAQs

Questions?

FAQs

Questions?

![]() Real

Estate

Real

Estate

![]() Shopping

Shopping

![]() Maps

Maps

![]() Bookstores

Bookstores

![]() Trains

Trains

![]() Busses

Busses

![]() Car

Rental

Car

Rental

![]() Hotels

Hotels

![]() News

(CT)

News

(CT)

![]() Medical

& Dental

Medical

& Dental

![]() Expat

Groups

Expat

Groups

![]() Maids

Maids

![]() Phone

#s

Phone

#s

EDUCATION

![]() Xiamen

University

Xiamen

University

![]() XIS(Int'l

School)

XIS(Int'l

School)

![]() Study

Mandarin

Study

Mandarin

![]() CSP(China

Studies)

CSP(China

Studies)

![]() Library

Library

![]() Museums

Museums

![]() History

History

DINING ![]() Tea

Houses

Tea

Houses

![]() Restaurants

Restaurants

![]() Asian

Asian

![]() Veggie

Veggie

![]() Junk

Food

Junk

Food

![]() Chinese

Chinese

![]() Italian

Italian

![]() International

International![]()

![]() Visas

4 aliens

Visas

4 aliens

RECREATION

![]() Massage!

Massage!

![]() Beaches

Beaches

![]() Fly

Kites

Fly

Kites

![]() Sports

Sports

![]() Boardwalk

Boardwalk

![]() Parks

Parks

![]() Pets

Pets

![]() Birdwatching

Birdwatching

![]() Kung

Fu

Kung

Fu ![]() Hiking

Hiking

![]() Music

Events

Music

Events

![]() Cinema

Cinema

![]() Festival&Culture

Festival&Culture

![]() Humor&

Humor&![]() Fun

Fotos

Fun

Fotos![]()

BUSINESS

![]() Doing

Business

Doing

Business

![]() Jobs!(teach/work)

Jobs!(teach/work)

![]() Hire

Workers

Hire

Workers

![]() Foreign

Companies

Foreign

Companies

![]() CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

![]() MTS(Translation)

MTS(Translation)

![]()

Back to Top