![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

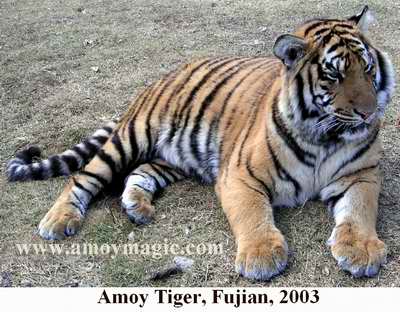

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

True Story of the Deadly

Amoy Vampire!

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

![]() "Amoy

Tiger Hunting"

"Amoy

Tiger Hunting"

![]() Click

for

Fujian's rare "Blue Tiger."

Click

for

Fujian's rare "Blue Tiger."

Click Here for

Caldwell's "Blue Tiger" ![]() Click

for

1918 Account of hunt for Blue Tiger

Click

for

1918 Account of hunt for Blue Tiger![]() Click

for True Discovery of Amoy Vampire! (1894)

Click

for True Discovery of Amoy Vampire! (1894)

Fujian are in a W. Fujian reserve on Meihua Mountain,

Fujian are in a W. Fujian reserve on Meihua Mountain,

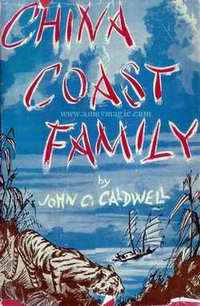

OUR FRIEND'S THE TIGERS

(Chapter 3 of "China Coast Family"

by John Caldwell)

Tiger,

Tiger burning bright

Tiger,

Tiger burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

THESE lines of Blake had greater significance for our family than for

any lover of poetry. Tigers came early into our lives and stayed there.

The wisdom of my Grandfather, and, added to that, Bishop Bashford's realization

that hunting could rightly be a pan of a missionary's life, brought fame

to Father as a mighty hunter, a man who dared to face the China tiger

in his lair. All the little Caldwells basked in reflected glory.

Most normal adults have anxiety dreams, dreams of falling

from planes, of not being ready for an emergency. For me, I dreamed for

years and well into adult life of being faced by a charging tiger and

finding my gun would not fire. I can remember hearing the deep-throated

roar of a tiger at night, and climbing into bed with Mother in terror.

I can remember stories told by Chek-saw, of little Chinese boys and girls

who were bad and were killed by the dread "laohu." I can remember

vividly the excited visits of people from the hills, reporting a tiger

raid and urging Father to put aside everything to go after the beast.

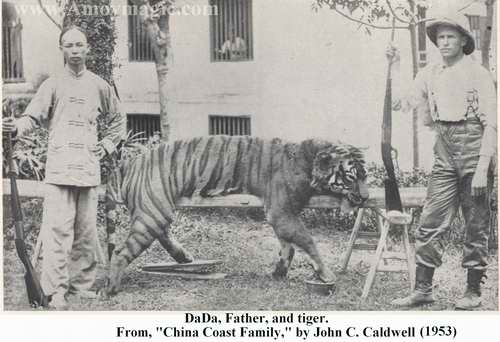

Above all I can remember the victorious occasions when Father and Da Da

returned from a successful hunt, the tiger draped over a stout bamboo

pole, borne by eight husky coolies. Following the animal was a vociferous

throng of Chinese, eager to see, more eager to snatch a tuft of hair or

sop up a bit of blood. Such items had great value as charms against the

evil spirits.Amoy

Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

Was not Mr. Caldwell of Futsing the famous killer of tigers? In China

our name became known up and down the coast. When we came to America on

furlough, fame followed us and Father was much interviewed and photographed.

One of my proudest childhood memories is of a furlough stay in Seattle.

An African big game movie was scheduled in Seattle's largest theater.

The manager borrowed the Caldwell tiger trophies to decorate the marquee.

We all had free passes to the show.

It was a childhood ambition of all three boys to shoot a tiger, just as

in America a boy might dream of making the big leagues. Morris was the

only one of us to make a killing. Da Da, too, became a tiger hunter in

his own right. Hunting changed his way of life. It even altered his physical

appearance. Amoy Magic

Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

For years, Da Da had worn the customary queue required by Chinese convention.

One day, when he was rising from a blind to fire at a charging tiger,

his queue became entangled in a thornbush. He dangled helplessly while

the tiger came on. Father dropped the beast only a length away. That night

Da Da appeared in the living room with a pair of shears. It was not necessary

for him to say a word. Father cut, and Da Da became the first man in his

village to break the rule of his forefathers.

We all heard the animals, saw their tracks, saw them brought home dead.

I recollect the day Mother looked out the window of the monastery where

we were spending the summer and saw three tigers basking in the sunlight

across the road. When Father returned and heard her story he was very

skeptical, but he took his gun and sallied forth to humor her.

Father took just six shells. Ten minutes after he left the monastery he

came face to face with five tigers. It took five shots to dispatch the

first one. The last shell accounted for one more.

Father hid in the grass while the remaining three animals sniffed their

dead and came all too close to sniffing him. After an hour or so they

wandered off, and Father came home somewhat subdued.

Mother was waiting for Father on the monastery steps.

"Harry, did I hear you shoot?" she asked.

"No," replied Father. "Those were just fire crackers at

a funeral. Two tigers have just died. If I'd listened to you there would

be more. We'll need about ten coolies to carry the bodies."

Americans think of China as a crowded land, with people packed like sardines.

The human population is large, but it is concentrated in villages and

cities. In Fukien, wilderness is always

close at hand. Even among the barren seacoast hills there arc valleys

and pockets of tall sword grass. As one advances inland the cover thickens

until there arc vast tracks of virgin hardwood-and-bamboo forests.Amoy

Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

While the tiger was lord of these hills, he was by no means the only animal

found. The hills abounded in game. There were leopards, wild hogs, wolves,

foxes, wild cats of a dozen varieties, deer ranging in size from tiny

antlered animals the height of a rabbit to the 600 pound sambar; serow,

a goat-like animal with donkey-cars and a flowing mane, and a dozen species

of pheasants. We hunted constantly. Instead of turkey for our Christmas

and Thanksgiving dinners, we had a choice of smoked or fresh wild boar

ham, a tender young muntjac deer, a wild goose, or a silver pheasant.

But it was the tiger that provided us with the greatest excitement, and

it was Father's tiger-killing rifle that became his passport into a hundred

adventures. Little wonder, either, that the tiger guns became something

more than inanimate objects. Father had several Savage rifles but to the

Chinese all were "La-hu cherngs"—the tiger guns. We children

named the guns, taking the names from our favorite childhood stories,

The Leather-stocking Tales by James Fennimore Cooper, Thus it was that

the tiger gun we loved and respected most became "Killdeer."

The tiger is both revered and feared in China. There has grown up around

him a mass of folk lore, superstition, and half-truth. According to ancient

legend, all true tigers have in their stomachs a blade of grass known

as the "pass-over-hunger grass." It is said that the gods provide

the grass as magic nourishment when the tiger is too old or sick to make

a kill, and that an animal without this blessing cannot be a true tiger.

Father's first two kills were immediately discredited on this score. There

were a number of local sages standing about in their long blue robes while

the animals were being skinned and dismembered. Not a blade of grass could

be found in cither beast. The sages announced to the assembled crowds

that these were not tigers at all, but some other evil animal masquerading

in tigers' guise. Amoy

Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

According to the wisdom of the sages, the Chinese character meaning "Lord"

or "Emperor" must be found in the markings of the forehead of

a tiger if it be a tiger of whom the devils and demons are afraid. Another

of Father's early kills, a magnificent male of which he was very proud,

disqualified. The two horizontal and one vertical white lines on the forehead

were not quite to the liking of the assembled scholars. They announced

that the animal could never have been born of tiger parents, but had come

out of some strange metamorphosis from an animal or fish living in the

sea.

Back to top

an

Copyright 2006 by Dr.

But it was not only the Chinese scholars who sought on occasion to discredit

our tigers. There was a talkative know-it-all in the foreign colony of

Foochow, His Britannic Majesty's Consul, who made much fun of Father's

first reports of tigers in the Fukien Hills.

Of all the many tigers which Father killed, the animal which provided

most satisfaction was the one we called The Consul's Tiger.

Tigers do not commonly kill human beings, being content to prey upon the

wildlife of their native haunts and an occasional goat or cow or dog.

But it seems that once a tiger has tasted human flesh, it will not be

satisfied with the normal food of the hills. The Consul's tiger was one

of these, appearing suddenly one spring in the Kutien hills. All around

that area there was an undertow of terror. It could be seen in the faces

of the men and the women in the villages or on the mountain trails; it

could be sensed in the stories that came into the big city. As it was

to happen often in the future when a man-eater was on the loose, the Chinese

magistrate of Kutien came in to talk with Father who had not yet killed

his first tiger. But his fame as a killer of wild hogs and deer, as possessor

of a magic American rifle, had reached the magistrate.M

"My records show that more than two hundred and fifty of our people

have been killed by this beast," said the magistrate. "Not to

speak of scores of cattle and goats."

"But what kind of monster is this killer?" Father asked. "The

villagers talk of a saber-toothed tiger who attacks and disappears again

with the speed of light. Some swear it is not flesh and blood but a phantom

beast begotten of the devils."

The magistrate shook his head sadly. "Teacher," he said, "When

you have lived long in this land you will know that many of us are like

children in some ways. I myself simply don't know what to make of it."

A couple of nights later, a Kutien family had just finished the evening

meal. The men of the house were sitting around the table, smoking. A child

had fallen asleep with its head against the table leg. All was peace and

quiet. Then something rushed through the door, upsetting the light and

throwing the house into darkness and chaos. The table flew through the

air and into the courtyard and when light was restored, the child was

gone.

Back to top

Copyright 2006 by Dr.

Men tending their herds or walking along the trails disappeared, or were

found mangled and half eaten. Crops were going untended; paralysis began

to settle on the hills. But it was not until the killer began seriously

to interfere with church work that Father decided to take time out for

the hunt. For the pastors of the Kutien area reported church attendance

falling off because people were afraid to stir from their houses.

A missionary from the hills of Tennessee has little background in tiger

lore, but by now Father was sure that the Kutien animal could only be

a tiger, and not likely of the saber-toothed variety cither. He sought

out the British Consul, a man who had spent years in India, to ask his

advice on the best methods of hunting. The Consul's reaction was not exactly

helpful.

"Tigers in Fukien?" he said.

"Only a missionary could dream up such a notion."

"But there has been a frightful loss of life," Father replied.

"And from the reports I get tigers are causing the trouble, and there

must be a number of them. I have heard similar reports from Futsing. If

you will give me some help and advice I believe I can dispose of the killers."

"Reverend, I don't think you'd know the difference between a tiger

and a civet cat if you met them both side by side."

Thus ended the interview with His Majesty's Consul, who offered no advice

and began to enjoy himself telling stones of Caldwell's tigers—or

wild cats.

Back to top

Father began preparations for hunting far bigger game than he had ever

shot in the mountains of Tennessee. All he knew of tigers was the little

he had read of big game hunts in India. In that land tigers are shot from

platforms on the backs of elephants, an animal conspicuous by its absence

in China. No elephants being available, he decided the next best thing

would be a stationary platform high in a tree. For bait, he reasoned that

in the manner of all cats, tigers would be much interested in fish. Since

Kutien was inland and no fresh fish available, he bought a case of sardines

and sallied forth on his first hunt, near a village that had been a center

of human and livestock killings.

Unfortunately the tigers of Fukien were

unsophisticated beasts, showing no interest in the sardines that Father

liberally smeared over the landscape. After repeated tries it became obvious

that new tactics, a new strategy must be developed. The method Father

and Da Da devised with success, and one they continued to use for years,

was simple, undramatic, but nonetheless dangerous.

Father had noted that goats were often the victims of tiger attack. He

bought a couple of kids, put them in a basket and set forth for the latest

known tiger lair. The goats were placed on a mountain path, and Father

and Da Da built a simple blind of sword grass nearby. As soon as the goats

felt deserted they began to bleat.

There was no sound of movement other than the bleating and scrambling

of the goats when suddenly the head of a tiger appeared in the overhanging

grass not more than fifteen yards away.

The tiger was moving towards the goats intent, alert, but heedless of

all except the meat at hand. In order to shoot, Father had to rise from

behind the blind of sword grass and as he did so the tiger bounded into

the jungle. Father's snap shot missed.

Back to top

The hunt was over for that day. But the identity of the marauder was no

longer in question. Come-uppance for the Consul was in sight. For days

Father and Da Da tried but without success. Several tigers came within

range but Father missed them all. These misses began to worry him a great

deal. He did not relish returning to Foochow and the Consul without something

to show. Just as important was the matter of losing face with the Chinese.

Already the local sages were talking, telling the people that the American's

rifle held no magic as far as the tiger was concerned.

Father was a crack shot. He couldn't understand the repeated misses. He

also began to wonder what would happen if he were charged by a tiger and

missed again. Then it occurred to him that the gun itself might be the

trouble. I Ie returned to the village, targeted his gun, and discovered

the trouble at once. The sights were badly out of line.

Father's host admitted then that he had caused the trouble. "Teacher,"

he said. "The first day you were here, after you had gone to bed

I showed the tiger gun to a friend. I dropped it upon the stones in the

courtyard. I did not realize that your magic gun could be harmed in this

manner."

It was late afternoon of a long day of hunting when success finally came.

Father and Da Da were getting ready to call it quits after having hid

for hours in a blind near the bait goats. As they rose to leave, Father

noticed a great and excited twittering of birds in a clump of sword grass

and brambles behind the blind. He was curious what was worrying the birds,

so he picked up a piece of brick from the wall of an ancient grave nearby

and tossed it into the brambles.

Back to top

He could have gotten no more violent reaction had he tossed a hand grenade.

The whole slope exploded in one huge charging tiger. The tiger had evidently

been working up his strategy for a charge at the goats, but when the brickbat

arrived in his hiding place he decided to charge his human foes instead.

Father dropped him with one shot, and there at last was the Consul's tiger!

There was great rejoicing in the village that night, and a feast was prepared.

After the thanks of the people, after one and all had opportunity to gloat

over their enemy, Da Da and Father started over the mountains to get a

down-river launch for Foochow. The launch stuck on a sand bar for three

hours, and all this time, the tiger, large in the first place, was on

the open deck, bloating in the sun. When they finally reached Foochow

the proportions of the animal were more those of a well-fed horse than

a tiger.

The launch landed at the busy customs jetty. The eager coolies started

up the hill to the foreign settlement, carrying the man-eater hung from

a bamboo pole. People began swarming from the tea houses, government offices,

and private dwellings. Father and Da Da led the way to the Mission Compound.

When they readied the top of the hill near the Foochow Club thousands

were in the procession. News swept ahead on the lips and feet of street

urchins. It was possible to let only a few hundred people at a time into

the Compound, so we admitted people in groups in order that all could

view the trophy. I saw Da Da near the gate and suspected that he was charging

admission to the show.

Back to top

Suddenly we heard a rattling at the gate and saw the British Consul peering

through the uprights. He was admitted and elbowed his way through the

crowd. He looked down at the great bloated cat and walked speechless around

it.

"Mr. Caldwcll," he finally said in awed tones. "I have

lived in India and have seen many Bengal tigers but never have I seen

one as big or beautiful as this."

"Is this a Tiger?" Father asked innocently.

"Is it a tiger! Why man it is the biggest tiger in creation."

"Why that just shows how an ignorant missionary can make a mistake,"

Father replied. "I have been under the impression that these things

were civet cats. Down country we have to chase them out of the back yard

every morning. I thought I'd bring one to Foochow just to show you fellows

what they look like."

That did it. The consul's sense of humor was not well developed. Even

the Chinese sensed that the proud Britisher was being ridiculed. He stared

a minute, then slammed out of the compound.

The Consul's tiger was large, it was Father's first, and its killing provided

him with sweet revenge. From then on no one doubted his tigers, his prowess,

or the magic of his gun.

He killed many more tigers as the years passed, most of them within a

few miles of our home in Futsing. Some of the hunts were routine, if one

can ever speak of tiger hunting in such terms. At other times there was

great excitement, near tragedy.

Once Father, on a preaching trip, entered a village where a sixteen year

old boy had just been killed by a tiger. He had only his shot gun with

him. The people were terrified, and he did not want to take the time to

return to Futsing for "Killdeer."

Back to top

http://www.amoymagic.mts.cn (in China) http://www.amoymagic.com (outside

China) Amoy

Magic -- Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

Then Father did a reckless and foolish thing. He was armed only with bird

shot for pheasant hunting. The village smithy melted down the shot, recasting

it into larger slugs. The ammunition Father had with him was sufficient

for just three of these home-made tiger loads. The goats were placed out

near the scene of attack, and Father had but a few minutes to wait.

This tiger wanted no goat lunch. Almost before Father had settled himself

the tiger came into view, bounding up a series of terraces directly at

him.

Father waited until the tiger's head appeared over the terrace directly

below, then fired twice into the great face just six feet away. The tiger's

head was cut to ribbons, but he did not fall. He stood there, dazed, putting

forward one foot, then withdrawing it, trying to get up courage for the

last charge. Father, all this while, was feverishly hunting through his

pockets for that one last load of slugs. He found the shell at last and

fired again at point-blank range.

[The Legendary Blue Tiger

of Fujian! Click Here for even more about him]

It was several years, and many tigers later, that stories began to drift

into the Futsing market place, even into Foochow, of an entirely new kind

of tiger, an enormous man-eater said to be shaped like a tiger but not

colored like a tiger. Some claimed it was a beautiful light blue or maltese

with black stripes, and stories of its ferocity soon spread through the

hill country.

Back to top

http://www.amoymagic.mts.cn (in China) http://www.amoymagic.com (outside

China) Amoy

Magic -- Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

When the stories began to gather substance, Father and Da Da started out

after the new beast. It soon came to be known as the Blue Tiger. But the

Blue Tiger had a charmed life, defying death. For years he hunted it.

As I grew older I joined the hunts, on several occasions seeing the beautiful

maltese hairs of the animal along the mountain trails. Da Da and Father

both saw it once in the great ravine near Da Da's village, but they were

without guns. On another occasion Father was in perfect position for a

sure shot. But the animal was stalking some little boys gathering wood

on the hillside. Father was afraid the animal, already close to its prey,

would injure the boys in its death struggle. So he came out of his hiding

place and the animal bounded away. Amoy

Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

Father felt sure the Blue Tiger was a freak of melanism, though if there

were more than a single animal, as the mountain people maintained, this

explanation was not entirely satisfactory. Its true identity was to remain

a mystery, and not to have solved that mystery was one of Father's greatest

regrets. Meanwhile stories of the Blue Tiger spread abroad and called

forth much excitement. One Chinese newspaper breathlessly announced that

Mr. Caldwell, the Great Tiger Hunter, had been offered $ io,ooo for the

hide of the Blue Tiger. Hunters of great renown began to write and telegraph

asking if they might come to Fukien, if

Father would take them on a hunt. I remember how thrilled we were when

we received a telegram from Douglas Fairbanks. I cannot remember what

transpired, but the great man did not come.

Others did come, some traveling thousands of miles. An American big game

hunter wired from India, offering to bring—and leave—his pack

of twenty huge hounds. Father was inclined to accept the offer until he

learned that the dogs required ten pounds of raw meat each daily to keep

in trim.

One reason for the global interest in our tigers was that the Fukien

breed turned out to be a new subspecies. Museums and laboratories were

interested in all its parts. The skin, bones, skulls, and internal organs

were in demand everywhere. And to all intents and purposes, Father had

discovered him.

Back to top

Of those who did come to hunt in our hills, some had luck, some did not.

But whether successful or not, all went away with unforgettable memories.

For there is nothing quite like the experience of sitting in a tiger blind

in a quiet ravine, or of still-hunting through the sword grass jungle.

Every sound becomes magnified, the imagination runs wild. When the coughing

roar of a tiger comes from close by, the blood fairly curdles. The tension

can become unbearable. One famous hunter bit through his lip as he and

Father sat in the blind, measuring the approach of a tiger by the twittering

of the little jungle titmouse, the tiger bird of the Fukien

jungles, which will follow and scold an approaching tiger or leopard.

In spite of all the tiger lore Father learned and passed on to us, we

knew full well that the unexpected could always happen. Sometimes the

tiger stalks the hunters instead of the goats; sometimes the trail it

should logically use is by-passed, and the animal comes in from an unexpected

quarter. Once Father was walking along the trail near our summer home,

unarmed and at dusk. Suddenly a tiger charged him down the hillside. By

good fortune Father was carrying his enormous black umbrella. He aimed

it, and opened and shut it with a great flapping. The tiger retreated

in the face of this strange and noisy weapon.

We boys were carefully instructed in what to do if charged by a tiger.

First, if at all possible, run down hill. A tiger's front legs are shorter

than its back legs, making down hill progress slow and awkward. If deep

water is nearby, make for it. Mu-king, one of our childhood hunting friends,

had been charged while working in rice fields. He dove into a storage

pond and the tiger, disliking water, refused to follow.

Back to top

Father never killed the Blue Tiger, but as the years passed, forty-eight

of the regular variety fell to him. In his later years he began to use

a new weapon, the motion picture camera. It was his hope to secure a complete

picture story of the animal. He was well on his way to success when war

caused sudden evacuation, and most of the footage secured at great danger

was left behind. But the animals he did shoot, whether with gun or camera,

provided us with fame and added income. Father's exploits attracted the

attention of a publisher, and his "Blue Tiger" became, briefly,

a best-seller in America. That was the only way in which tiger hunting

benefited us materially.

Father's hunting was done in the spirit of the 117th Psalm. His gun did

more than effectively reduce the man-eating tigers of South China. It

brought us many and varied friendships. It was the key to the hearts of

the mountain people, making possible the building of new churches and

new schools. It even brought better health along the Coast. For the Lister

Institute in Shanghai was to discover the source of the deadly fluke in

the human body through a study of the tiger organs Father contributed

to research.

Thus it was that the rifle, together with the Bible, became a formidable

weapon against the superstitions and diseases of the China Coast.

Back to top

Adapted from “Sport in Amoy,”

China Review, Vol. 22 No. 5 (1897) By H. R. Bruce

But

the crowning sport with which the name of Amoy

is associated is the pursuit of that king of the jungle, the wily tiger.

Tigers abound more or less all along the coast of China, and

native trappers declare that they are more abundant in ‘Kwang Tung’

province than in Fokien.

These trappers travel over several provinces in search of tiger lairs,

and having discovered one they find that the tiger follows the same track

in entering and leaving. They survey this track, select some point where

the track dips a little below the ground on one side or the other.

Back to topde

to Xiamen and Fujian Copyright 2006 by Dr.

On this higher ground they dig a hole like a grave and fix therein a very

powerful bow with a poisoned shaft protruding through a small tunnel that

connects the grave with the track. The bow is fired by a small thread

fixed across the path, so as to catch a passing tiger’s chest, and

the poison is so effective that the wounded beast seldom gets away.

The tiger is a valuable prize, he is good medicine from his whiskers to

the tip of his tail, and all who covet strength, courage or ferocity compete

for a portion of the specific. Moreover, there is no adulteration act

to ensure that all that is sold as tiger, is really tiger, so that with

the help of an ancient buffalo, or of a dead horse, a tiger of 300 pounds

weight gives fully 1,000 pounds retail weight.

The natives have curious ideas about tigers occupying

lairs in their neighborhood. If a man has been killed they welcome the

foreign sportsman most cordially, and chin-chin him as the savior of the

people, but if the tiger has not been known to take human life they are

disposed to propitiate him, and condemn the folly of enraging him and

perhaps converting a good dispositioned beast into a maneater. Then again

they will say, ‘What is the use of shooting him, two new tigers

will at once occupy his den.’

Back to top

Sometimes a tiger has the character of never harming the villagers who

are his neighbors; although he eats up strangers and travellers by the

score, the villagers are quite sure of their own safety. If one stays

in the village for a few days another reason for their immunity suggests

itself. Owing to their propinquity to a permanent tiger lair they have

inherited habits of early hours at night, and late hours in the morning,

that give the poor tiger no chance, so he has to fall back on benighted

strangers with less regular habits.

All

Amoy tigers are village prowlers, and man-eaters.

There is no game of any sort: goats, pigs and cows are carefully pounded

at night, so that probably village dogs comprise 5/6ths of the necessary

support for the tigers of this province. Their hunting ground being so

much among the haunts of men, tigers, after dusk at any rate, have lost

all instinctive dread of man, and the sounds and odours of humanity, and

will stroll up a village street soon after bed-time, and break open a

door in search of pig, or dog. It is by no means an uncommon occurrence

for a tiger to take a man out of his bed, and in the hot weather many

lives are lost by sleeping in the doorway, and under the eaves.

It may be asked how it comes to pass that sportsmen bag tigers in Amoy,

and not at other ports. For thirty years there have been casual hunts

for tigers, but it was only some ten years ago that that indefatigable

sport Mr. A. L. B. Allen succeeded in proving that patience, perseverance,

lots of time, and good nerves could bring a tiger to the bag. Since then

the sport has been keenly pursued, and that indomitable old shikaree Mr.

Frank Leyburn heads the list with about 20 ‘kills.’

Back to top

06

by Dr.

There is not much jungle within 20 miles of Amoy.

The tigers lie up in subterranean passages in the rocky nullahs common

to every hill-side. To drive them out of these caves the native hunters

fearlessly enter armed with spears, and torches fixed on long bamboos.

If Mr. Stripes has a bolt-hole he will bolt and come under the guns outside;

but if caught in a cul-de-sac the sportsman must crawl into the cave,

wriggle past the hunters and shoot at 20 years or less, usually a tame

performance compared to an encounter in the open.

Of course much rough work, and many discomforts attend tiger shooting,

but on the other hand there are many compensations which make a trip enjoyable.

If one is lucky enough to put up in one of the mountain temples, far from

the madding crow, and commanding a wide view of the neighbouring valleys,

with their unrivalled agriculture feeding a thousand to the square mile,

the fresh air and charming scenery are enough to live on. Again to acquire

a good knowledge of the country, and to study the habits of the people

is always of interest, and although one cannot hope to bag a tiger every

week, when the lucky day comes, there is a decided feeling that the noble

sport is well worth our most ardent devotion.

Back

to top

The

Maltese Tiger or Blue Tiger (This section from Wikipedia)

Click Here to Read Caldwell's Account of the

Blue Tiger.

(Panthera

tigris melitensis) An extremely rare breed of tiger that only lives in

the Fujian Province Fujian and has only been sighted on a few occasions.

It is said to have bluish fur with dark gray stripes.American Methodist

missionary Harry R. Caldwell described a clear sighting of a tiger colored

in deep shades of blue and maltese (bluish-gray) while in China. Caldwell

was an experienced tiger spotter and hunter; during his time in China,

he shot literally scores of the big cats. In September of 1910, Caldwell

was watching a goat in the Fujian Province. A tiger was pointed out, but

at first glance Caldwell believed it to be a man dressed in blue crouching

in some brush. Caldwell described his second glance, "...I saw the

huge head of the tiger above the blue which had appeared to me to be the

clothes of a man. What I had been looking at was the chest and belly of

the animal." He raised his gun to fire, but two small children were

in the way. During the time it took for him to alter position, the Maltese

Tiger vanished. Caldwell described the tiger as having a maltese base

color which changed to deep blue on the undersides. The stripes appeared

to be similar to those on a Bengal Tiger. He named the tiger "Bluebeard".

Though he never caught the cat, villagers confirmed the presence of 'black

devils' roaming the area.

Other blue tiger sightings

Other

very occasional sightings have been claimed of bluish-toned tigers, particularly

in the Fujian Province. There was one report from the son of a US Army

soldier who served in Korea during the Korean War. His father is certain

he sighted a blue tiger in the mountains there, near what is now the Demilitarized

Zone. In support of the blue tiger theory, maltese-colored cats certainly

do exist. The most common is a domestic breed, but blue bobcats and lynxes

have also been recorded and there is a little-known genetic combination

which results in blue tonings. On top of this, for a very long time experts

considered the black tiger mythical. Several pelts have proven otherwise.

Something we can probably conclude is that Maltese tigers were of the

South Chinese subspecies. Fujian Province is the area most famed for the

blue colouring and that was once a stronghold for this tiger. But few,

if any, of these tigers exist in the wild now and the number of blue sightings

is out of proportion to the tiny population (perhaps 30 cats) which may

remain. Admittedly, inbreeding produces some odd colour combinations,

but this usually tends towards melanism; blue is not known to be a side

effect.

[End of Extract from Wikipedia]

Click Here to read Caldwell's account of his

Blue Tiger sighting.

Back to top

CHAPTER

VI HUNTING THE "GREAT INVISIBLE"

Click Here for CHAPTER VII THE BLUE TIGER

Take

from "CAMPS AND TRAILS IN CHINA-A NARRATIVE OF EXPLORATION, ADVENTURE,

AND SPORT IN LITTLE-KNOWN CHINA" BY ROY CHAPMAN ANDREWS, M.A. AND

YVETTE BORUP ANDREWS, 1918

From the Project Gutenberg E-Text

# 12296 Click Here

to Download Entire E-Book

Click Here to

Support Project Gutenberg (18,000+ Free E-books and counting!)

For many years before Mr. Caldwell went to Yen-ping he had been stationed at the city of Futsing, about thirty miles from Foochow. Much of his work consisted of itinerant trips during which he visited the various mission stations under his charge. He almost invariably went on foot from place to place and carried with him a butterfly net and a rifle, so that to so keen a naturalist each day's walk was full of interest.

The country was infested with man-eating tigers, and very often the villagers implored him to rid their neighborhood of some one of the yellow raiders which had been killing their children, pigs, or cattle. During ten years he had killed seven tigers in the Futsing region. He often said that his gun had been just as effective in carrying Christianity to the natives as had his evangelistic work. Although Mr. Caldwell has been especially fortunate and has killed his tigers without ever really hunting them, nevertheless it is a most uncertain sport as we were destined to learn. The tiger is the "Great Invisible"--he is everywhere and nowhere, here today and gone tomorrow. A sportsman in China may get his shot the first day out or he may hunt for weeks without ever seeing a tiger even though they are all about him; and it is this very uncertainty that makes the game all the more fascinating.

The

part of Fukien Province about Futsing includes

mountains of considerable height, many of which are planted with rice

and support a surprising number of Chinese who are grouped in closely

connected villages. While the cultivated valleys afford no cover for tiger

and the mountain slopes themselves are usually more or less denuded of

forest, yet the deep and narrow ravines, choked with sword grass and thorny

bramble, offer an impenetrable retreat in which an animal can sleep during

the day without fear of being disturbed. It is possible for a man to make

his way through these lairs only by means of the paths and tunnels which

have been opened by the tigers themselves.

Back to top

Mr. Caldwell's usual method of hunting was to lead a goat with one or two kids to an open place where they could be fastened just outside the edge of the lair, and then to conceal himself a few feet away. The bleating of the goats would usually bring the tiger into the open where there would be an opportunity for a shot in the late afternoon.

Mr. Caldwell's first experience in hunting tigers was with a shotgun at the village of Lung-tao. His burden-bearers had not arrived with the basket containing his rifle, and as it was already late in the afternoon, he suggested to Da-Da, the Chinese boy who was his constant companion, that they make a preliminary inspection of the lair even though they carried only shotguns loaded with lead slugs about the size of buckshot.

They

tethered a goat just outside the edge of the lair and the tiger responded

to its bleating almost immediately. Caldwell did not see the animal until

it came into the open about fifty yards away and remained in plain view

for almost half an hour. The tiger seemed to suspect danger and crouched

on the terrace, now and then putting his right foot forward a short distance

and drawing it slowly back again. He had approached along a small trail,

but before he could reach the goat it was necessary to cross an open space

a few yards in width, and to do this the animal flattened himself like

a huge striped serpent. His head was extended so that the throat and chin

were touching the ground, and there was absolutely no motion of the body

other than the hips and shoulders as the beast slid along at an amazingly

rapid rate. But at the instant the cat gained the nearest cover it made

three flying leaps and landed at the foot of the terrace upon which the

goat was tied.

Back to top

"Just then he saw me," said Mr. Caldwell, "and slowly pushed his great black-barred face over the edge of the grass not fifteen feet away.

"I fired point-blank at his head and neck. He leaped into the air with the blood spurting over the grass, and fell into a heap, but gathered himself and slid down over the terraces. As he went I fired a second load of slugs into his hip. He turned about, slowly climbed the hill parallel with us, and stood looking back at me, his face streaming with blood.

"I was fumbling in my coat trying to find other shells, but before I could reload the gun he walked unsteadily into the lair and lay down. It was already too dark to follow and the next morning a bloody trail showed where he had gone upward into the grass. Later, in the same afternoon, he was found dead by some Chinese more than three miles away."

During his many experiences with the Futsing tigers Mr. Caldwell has learned much about their habits and peculiarities, and some of his observations are given in the following pages.

"The tiger is by instinct a coward when confronted by his greatest enemy--man. Bold and daring as he may be when circumstances are in his favor, he will hurriedly abandon a fresh kill at the first cry of a shepherd boy attending a flock on the mountain-side and will always weigh conditions before making an attack. If things do not exactly suit him nothing will tempt him to charge into the open upon what may appear to be an isolated and defenseless goat.

"An experience I had in April, 1910, will illustrate this point. I led a goat into a ravine where a tiger which had been working havoc among the herds of the farmers was said to live. This animal only a few days previous to my hunt had attacked a herd of cows and killed three of them, but on this occasion the beast must have suspected danger and was exceedingly cautious. He advanced under cover along a trail until within one hundred feet of the goat and there stopped to make a survey of the surroundings. Peering into the valley, he saw two men at a distance of five hundred yards or more cutting grass and, after watching intently for a time, the great cat turned and bounded away into the bushes.

"On another occasion this tiger awaited an opportunity to attack a cow which a farmer was using in plowing his field. The man had unhitched his cow and squatted down in the rice paddy to eat his mid-day meal, when the tiger suddenly rushed from cover and killed the animal only a few yards behind the peasant. This shows how daring a tiger may be when he is able to strike from the rear, and when circumstances seem to favor an attack. I have known tigers to rush at a dog or hog standing inside a Chinese house where there was the usual confusion of such a dwelling, and in almost every instance the victim was killed, although it was not always carried away.Back to top

"There is probably no creature in the wilds which shows such a combination of daring strategy and slinking cowardice as the tiger. Often courage fails him after he has secured his victim, and he releases it to dash off into the nearest wood.

"I knew of two Chinese who were deer hunting on a mountain-side when a large tiger was routed from his bed. The beast made a rushing attack on the man standing nearest to the path of his retreat, and seizing him by the leg dragged him into the ravine below. Luckily the man succeeded in grasping a small tree whereupon the tiger released his hold, leaving his victim lying upon the ground almost paralyzed with pain and fear.

"A group of men were gathering fuel on the hills near Futsing when a tiger which had been sleeping in the high grass was disturbed. The enraged beast turned upon the peasants, killing two of them instantly and striking another a ripping blow with his paw which sent him lifeless to the terrace below. The beast did not attempt to drag either of its victims into the bush or to attack the other persons near by.

"The strength and vitality of a full grown tiger are amazing. I had occasion to spend the night a short time ago in a place where a tiger had performed some remarkable feats. Just at dusk one of these marauders visited the village and discovered a cow and her six-months-old calf in a pen which had been excavated in the side of a hill and adjoined a house. There was no possible way to enter the enclosure except by a door opening from the main part of the dwelling or to descend from above. The tiger jumped from the roof upon the neck of the heifer, killing it instantly, and the inmates of the house opened the door just in time to see the animal throw the calf out bodily and leap after it himself. I measured the embankment and found that the exact height was twelve and a half feet.

"The same tiger one noon on a foggy day attacked a hog, just back of the village and carried it into the hills. The villagers pursued the beast and overtook it within half a mile. When the hog, which dressed weighed more than two hundred pounds, was found, it had no marks or bruises upon it other than the deep fang wounds in the neck. This is another instance where courage failed a tiger after he had made off with his kill to a safe distance. The Chinese declare that when carrying such a load a tiger never attempts to drag its prey, but throws it across its back and races off at top speed.

"The

finest trophy taken from Fukien Province

in years I shot in May, 1910. Two days previous to my hunt this tiger

had killed and eaten a sixteen-year-old boy. I happened to be in the locality

and decided to make an attempt to dispose of the troublesome beast. Obtaining

a mother goat with two small kids, I led them into a ravine near where

the boy had been killed. The goat was tied to a tree a short distance

from the lair, and the kids were concealed in the tall grass well in toward

the place where the tiger would probably be. I selected a suitable spot

and kneeled down behind a bank of ferns and grass. The fact that one may

be stalked by the very beast which one is hunting adds to the excitement

and keeps one's nerves on edge. I expected that the tiger would approach

stealthily as long as he could not see the goat, as the usual plan of

attack, so far as my observation goes, is to creep up under cover as far

as possible before rushing into the open. In any case the tiger would

be within twenty yards of me before it could be seen.

Back

to top c.

"For more than two hours I sat perfectly still, alert and waiting,

behind the little blind of ferns and grass. There was nothing to break

the silence other than the incessant bleating of the goats and the unpleasant

rasping call of the mountain jay. I had about given up hope of a shot

when suddenly the huge head of the man-eater emerged from the bush, exactly

where I had expected he would appear and within fifteen feet of the kids.

The back, neck, and head of the beast were in almost the same plane as

he moved noiselessly forward.

"I had implicit confidence in the killing power of the gun in my hand, and at the crack of the rifle the huge brute settled forward with hardly a quiver not ten feet from the kids upon which he was about to spring. A second shot was not necessary but was fired as a matter of precaution as the tiger had fallen behind rank grass, and the bullet passed through the shoulder blade lodging in the spine. The beast measured more than nine feet and weighed almost four hundred pounds.

"Upon hearing the shots the villagers swarmed into the ravine, each eager not so much to see their slain tormentor as to gather up the blood. But little attention was paid to the tiger until every available drop was sopped up with rags torn from their clothing, whilst men and children even pulled up the blood-soaked grass. I learned that the blood of a tiger is used for two purposes. A bit of blood-stained cloth is tied about the neck of a child as a preventive against either measles or smallpox, and tiger flesh is eaten for the same purpose. It is also said that if a handkerchief stained with tiger blood is waved in front of an attacking dog the animal will slink away cowed and terrified.

"From the Chinese point of view the skin is not the most valuable part of a tiger. Almost always before a hunt is made, or a trap is built, the villagers burn incense before the temple god, and an agreement is made to the effect that if the enterprise be successful the skin of the beast taken becomes the property of the gods. Thus it happens that in many of the temples handsome tiger-skin robes may be found spread in the chair occupied by the noted 'Duai Uong,' or the god of the land. When a hunt is successful, the flesh and bones are considered of greatest value, and it often happens that a number of cows are killed and their flesh mixed with that of the tiger to be sold at the exorbitant price cheerfully paid for tiger meat. The bones are boiled for a number of days until a gelatine-like product results, and this is believed to be exceptionally efficacious medicine.

"Notwithstanding

the danger of still-hunting a tiger in the tangle of its lair, one cannot

but feel richly rewarded for the risk when one begins to sum up one's

observations. The most interesting result of investigating an oft-frequented

lair is concerning the animal's food. That a tiger always devours its

prey upon the spot where it is taken or in the adjacent bush is an erroneous

idea. This is often true when the kill is too heavy to be carried for

a long distance, but it is by no means universally so. Not long ago the

remains of a young boy were found in a grave adjacent to a tiger's lair

a few miles from Futsing city. No child had been reported missing in the

immediate neighborhood and everything indicated that the boy had been

brought alive to this spot from a considerable distance. The sides of

the grave were besmeared with the blood of the unfortunate victim, indicating

that the tiger had tortured it just as a cat plays with a mouse as long

as it remains alive.

Back to top

"In the lair of a tiger there are certain terraces,

or places under overhanging trees, which are covered with bones, and are

evidently spots to which the animal brings its prey to be devoured. On

such a terrace one will find the remains of deer, wild hog, dog, pig,

porcupine, pangolin, and other animals both domestic and wild. A fresh

kill shows that with its rasp-like tongue the tiger licks off all the

hair of its prey before devouring it and the hair will be found in a circle

around what remains of the kill. The Chinese often raid a lair in order

to gather up the quills of the porcupine and the bony scales of the pangolin

which are esteemed for medicinal purposes.

"In addition to the larger animals, tigers feed upon reptiles and frogs which they find among the rice fields. On the night of April 22, 1914, a party of frog catchers were returning from a hunt when the man carrying the load of frogs was attacked by a tiger and killed. The animal made no attempt to drag the man away and it would appear that it was attracted by the croaking of the frogs."

"One often finds trees 'marked' by tigers beside some trail or path in, or adjacent to, a lair. Catlike, the tiger measures its full length upon a tree, standing in a convenient place, and with its powerful claws rips deeply through the bark. This sign is doubly interesting to the sportsman as it not only indicates the presence of a tiger in the immediate vicinity but serves to give an accurate idea as to the size of the beast. The trails leading into a lair often are marked in a different way. In doing this the animal rakes away the grass with a forepaw and gathers it into a pile, but claw prints never appear."

Back

to top

CHAPTER VII THE BLUE TIGER

After one has traveled in a Chinese sampan for several days the prospect of a river journey is not very alluring but we had a most agreeable surprise when we sailed out of Foochow in a chartered house boat to hunt the "blue tiger" at Futsing. In fact, we had all the luxury of a private yacht, for our boat contained a large central cabin with a table and chairs and two staterooms and was manned by a captain and crew of six men--all for $1.50 per day!

In the evening we talked of the blue tiger for a long time before we spread our beds on the roof of the boat and went to sleep under the stars. We left the boat shortly after daylight at Daing-nei for the six-mile walk to Lung-tao. To my great surprise the coolies were considerably distressed at the lightness of our loads. In this region they are paid by weight and some of the bearers carry almost incredible burdens. As an example, one of our men came into camp swinging a 125-pound trunk on each end of his pole, laughing and chatting as gayly as though he had not been carrying 250 pounds for six miles under a broiling sun.

Mr. Caldwell's Chinese hunter, Da-Da, lived at Lung-tao and we found his house to be one of several built on the outskirts of a beautiful grove of gum and banyan trees. Although it was exceptionally clean for a Chinese dwelling, we pitched our tents a short distance away. At first we were somewhat doubtful about sleeping outside, but after one night indoors we decided that any risk was preferable to spending another hour in the stifling heat of the house.

It was probable that a tiger would be so suspicious of the white tents that it would not attack us, but nevertheless during the first nights we were rather wakeful and more than once at some strange night sound seized our rifles and flashed the electric lamp into the darkness.

Tigers often come into this village. Only a few hundred yards from our camp site, in 1911, a tiger had rushed into the house of one of the peasants and attempted to steal a child that had fallen asleep at its play under the family table. All was quiet in the house when suddenly the animal dashed through the open door. The Chinese declare that the gods protected the infant, for the beast missed his prey and seizing the leg of the table against which the baby's head was resting, bolted through the door dragging the table into the courtyard.

This

was the work of the famous "blue tiger" which we had come to

hunt and which had on two occasions been seen by Mr. Caldwell. The first

time he heard of this strange beast was in the spring of 1910. The animal

was reported as having been seen at various places within an area of a

few miles almost simultaneously and so mysterious were its movements that

the Chinese declared it was a spirit of the devil. After several unsuccessful

hunts Mr. Caldwell finally saw the tiger at close range but as he was

armed with only a shotgun it would have been useless to shoot.

Back to top

His second view of the beast was a few weeks later and in the same place. I will give the story in his own words:

"I selected a spot upon a hill-top and cleared away the grass and ferns with a jack-knife for a place to tie the goat. I concealed myself in the bushes ten feet away to await the attack, but the unexpected happened and the tiger approached from the rear.

"When I first saw the beast he was moving stealthily along a little trail just across a shallow ravine. I supposed, of course, that he was trying to locate the goat which was bleating loudly, but to my horror I saw that he was creeping upon two boys who had entered the ravine to cut grass. The huge brute moved along lizard-fashion for a few yards and then cautiously lifted his head above the grass. He was within easy springing distance when I raised my rifle, but instantly I realized that if I wounded the animal the boys would certainly meet a horrible death.

"Tigers are usually afraid of the human voice so instead of firing I stepped from the bushes, yelling and waving my arms. The huge cat, crouched for a spring, drew back, wavered uncertainly for a moment, and then slowly slipped away into the grass. The boys were saved but I had lost the opportunity I had sought for over a year.

"However, I had again seen the animal about which so many strange tales had been told. The markings of the beast are strikingly beautiful. The ground color is of a delicate shade of maltese, changing into light gray-blue on the underparts. The stripes are well defined and like those of the ordinary yellow tiger."

Before I left New York Mr. Caldwell had written me repeatedly urging me to stop at Futsing on the way to Yün-nan to try with him for the blue tiger which was still in the neighborhood. I was decidedly skeptical as to its being a distinct species, but nevertheless it was a most interesting animal and would certainly be well worth getting.

I believed then, and my opinion has since been strengthened, that it is a partially melanistic phase of the ordinary yellow tiger. Black leopards are common in India and the Malay Peninsula and as only a single individual of the blue tiger has been reported the evidence hardly warrants the assumption that it represents a distinct species.

We hunted the animal for five weeks. The brute ranged in the vicinity of two or three villages about seven miles apart, but was seen most frequently near Lung-tao. He was as elusive as a will o' the wisp, killing a dog or goat in one village and by the time we had hurried across the mountains appearing in another spot a few miles away, leaving a trail of terrified natives who flocked to our camp to recount his depredations. He was in truth the "Great Invisible" and it seemed impossible that we should not get him sooner or later, but we never did.

Once we missed him by a hair's breadth through sheer bad luck, and it was only by exercising almost superhuman restraint that we prevented ourselves from doing bodily harm to the three Chinese who ruined our hunt. Every evening for a week we had faithfully taken a goat into the "Long Ravine," for the blue tiger had been seen several times near this lair. On the eighth afternoon we were in the "blind" at three o'clock as usual. We had tied a goat to a tree nearby and her two kids were but a few feet away.

The grass-filled lair lay shimmering in the breathless heat, silent save for the echoes of the bleating goats. Crouched behind the screen of branches, for three long hours we sat in the patchwork shade,--motionless, dripping with perspiration, hardly breathing,--and watched the shadows steal slowly down the narrow ravine.

Back

to top

It was a wild place which seemed to have

been cut out of the mountain side with two strokes of a mighty ax and

was choked with a tangle of thorny vines and sword grass. Impenetrable

as a wall of steel, the only entrance was by the tiger tunnels which drove

their twisting way through the murderous growth far in toward its gloomy

heart.

The shadows had passed over us and just reached a lone palm tree on the opposite hillside. By that I knew it was six o'clock and in half an hour another day of disappointment would be ended. Suddenly at the left and just below us there came the faintest crunching sound as a loose stone shifted under a heavy weight; then a rustling in the grass. Instantly the captive goat gave a shrill bleat of terror and tugged frantically at the rope which held it to the tree.

At the first sound Harry had breathed in my ear "Get ready, he's coming." I was half kneeling with my heavy .405 Winchester pushed forward and the hammer up. The blood drummed in my ears and my neck muscles ached with the strain but I thanked Heaven that my hands were steady.

Caldwell sat like a graven image, the stock of his little 22 caliber high power Savage nestling against his cheek. Our eyes met for an instant and I knew in that glance that the blue tiger would never make another charge, for if I missed him, Harry wouldn't. For ten minutes we waited and my heart lost a beat when twenty feet away the grass began to move again--but rapidly and up the ravine.

I saw Harry watching the lair with a puzzled look which changed to one of disgust as a chorus of yells sounded across the ravine and three Chinese wood cutters appeared on the opposite slope. They were taking a short cut home, shouting to drive away the tigers--and they had succeeded only too well, for the blue tiger had slipped back to the heart of the lair from whence he had come.

He had been nearly ours and again we had lost him! I felt so badly that I could not even swear and it wasn't the fact that Harry was a missionary which kept me from it, either. Caldwell exclaimed just once, for his disappointment was even more bitter than mine; he had been hunting this same tiger off and on for six years.

It was useless for us to wait longer that evening and we pushed our way through the sword grass to the entrance of the tunnel down which the tiger had come. There in the soft earth were the great footprints where he had crouched at the entrance to take a cautious survey before charging into the open.

As we looked, Harry suddenly turned to me and said: "Roy, let's go into the lair. There is just one chance in a thousand that we may get a shot." Now I must admit that I was not very enthusiastic about that little excursion, but in we went, crawling on our hands and knees up the narrow passage. Every few feet we passed side branches from the main tunnel in any one of which the tiger might easily have been lying in wait and could have killed us as we passed. It was a foolhardy thing to do and I am free to admit that I was scared. It was not long before Harry twisted about and said: "Roy, I haven't lost any tigers in here; let's get out." And out we came faster than we went in.

Back

to top

This was only one of the times when the

"Great Invisible" was almost in our hands. A few days later

a Chinese found the blue tiger asleep under a rice bank early in the afternoon.

Frightened almost to death he ran a mile and a half to our camp only to

find that we had left half an hour before for another village where the

brute had killed two wild cats early in the morning.

Again, the tiger pushed open the door of a house at daybreak just as the members of the family were getting up, stole a dog from the "heaven's well," dragged it to a hillside and partly devoured it. We were in camp only a mile away and our Chinese hunters found the carcass on a narrow ledge in the sword grass high up on the mountain side. The spot was an impossible one to watch and we set a huge grizzly bear trap which had been carried with us from New York.

It seemed out of the question for any animal to return to the carcass of the dog without getting caught and yet the tiger did it. With his hind quarters on the upper terrace he dropped down, stretched his long neck across the trap, seized the dog which had been wired to a tree and pulled it away. It was evident that he was quite unconscious of the trap for his fore feet had actually been placed upon one of the jaws only two inches from the pan which would have sprung it.

One afternoon we responded to a call from Bui-tao, a village seven miles beyond Lung-tao, where the blue tiger had been seen that day. The natives assured us that the animal continually crossed a hill, thickly clothed with pines and sword grass just above the village and even though it was late when we arrived Harry thought it wise to set the trap that night.

It was pitch dark before we reached the ridge carrying the trap, two lanterns, an electric flash-lamp and a wretched little dog for bait. We had been engaged for about fifteen minutes making a pen for the dog, and Caldwell and I were on our knees over the trap when suddenly a low rumbling growl came from the grass not twenty feet away. We jumped to our feet just as it sounded again, this time ending in a snarl. The tiger had arrived a few moments too early and we were in the rather uncomfortable position of having to return to the village by way of a narrow trail through the jungle. With our rifles ready and the electric lamp cutting a brilliant path in the darkness we walked slowly toward the edge of the sword grass hoping to see the flash of the tiger's eyes, but the beast backed off beyond the range of the light into an impenetrable tangle where we could not follow. Apparently he was frightened by the lantern, for we did not hear him again.

After nearly a month of disappointments such as these Mr. Heller joined us at Bui-tao with Mr. Kellogg. Caldwell thought it advisable to shift camp to the Ling-suik monastery, about twelve miles away, where he had once spent a summer with his family and had killed several tigers. This was within the blue tiger's range and, moreover, had the advantage of offering a better general collecting ground than Bui-tao; thus with Heller to look after the small mammals we could begin to make our time count for something if we did not get the tiger.

Ling-suik is a beautiful temple, or rather series of temples, built into a hillside at the end of a long narrow valley which swells out like a great bowl between bamboo clothed mountains, two thousand feet in height. On his former visit Mr. Caldwell had made friends with the head priest and we were allowed to establish ourselves upon the broad porch of the third and highest building. It was an ideal place for a collecting camp and would have been delightful except for the terrible heat which was rendered doubly disagreeable by the almost continual rain.

The

priests who shuffled about the temples were a hard lot. Most of them were

fugitives from justice and certainly looked the part, for a more disreputable,

diseased and generally undesirable body of men I have never seen.

Back to top

Our stay at Ling-suik was productive and

the temple life interesting. We slept on the porch and each morning, about

half an hour before daylight, the measured strokes of a great gong sounded

from the temple just below us. Boom--boom--boom--boom it went, then rapidly

bang, bang, bang. It was a religious alarm clock to rouse the world.

A little later when the upturned gables and twisted dolphins on the roof had begun to take definite shape in the gray light of the new day, the gong boomed out again, doors creaked, and from their cell-like rooms shuffled the priests to yawn and stretch themselves before the early service. The droning chorus of hoarse voices, swelling in a meaningless half-wild chant, harmonized strangely with the romantic surroundings of the temple and become our daily matin and evensong.

At the first gong we slipped from beneath our mosquito nets and dressed to be ready for the bats which fluttered into the building to hide themselves beneath the tiles and rafters. When daylight had fully come we scattered to the four winds of heaven to inspect traps, hunt barking deer, or collect birds, but gathered again at nine o'clock for breakfast and to deposit our spoil. Caldwell and I always spent the afternoon at the blue tiger's lair but the animal had suddenly shifted his operations back to Lung-tao and did not appear at Ling-suik while we were there.

Our work in Fukien taught us much that may be of help to other naturalists who contemplate a visit to this province. We satisfied ourselves that summer collecting is impracticable, for the heat is so intense and the vegetation so heavy that only meager results can be obtained for the efforts expended. Continual tramping over the mountains in the blazing sun necessarily must have its effect upon the strongest constitution, and even a man like Mr. Caldwell, who has become thoroughly acclimated, is not immune.

Both Caldwell and I lost from fifteen to twenty pounds in weight during the time we hunted the blue tiger and each of us had serious trouble from abscesses. I have never worked in a more trying climate--even that of Borneo and the Dutch East Indies where I collected in 1909-10, was much less debilitating than Fukien in the summer. The average temperature was about 95 degrees in the shade, but the humidity was so high that one felt as though one were wrapped in a wet blanket and even during a six weeks' rainless period the air was saturated with moisture from the sea-winds.

In

winter the weather is raw and damp, but collecting then would be vastly

easier than in summer, not only on account of climatic conditions, but

because much of the vegetation disappears and there is an opportunity

for "still hunting."

Back to top

Trapping for small mammal is especially

difficult because of the dense population. The mud dykes and the rice

fields usually are covered with tracks of civets, mongooses, and cats

which come to hunt frogs or fish, but if a trap is set it either catches

a Chinaman or promptly is stolen. Moreover, the small mammals are neither

abundant nor varied in number of species, and the larger forms, such as

tiger, leopard, wild pig and serow are exceedingly difficult to kill.

While our work in the province was done during an unfavorable season and in only two localities, yet enough was seen of the general conditions to make it certain that a thorough zoölogical study of the region would require considerable time and hard work and that the results, so far as a large collection of mammals is concerned, would not be highly satisfactory. Work in the western part of the province among the Bohea Hills undoubtedly would be more profitable, but even there it would be hardly worth while for an expedition with limited time and money.

Bird life is on a much better footing, but the ornithology of Fukien already has received considerable attention through the collections of Swinhoe, La Touche, Styan, Ricketts, Caldwell and others, and probably not a great number of species remain to be described.

Much work could still be done upon the herpetology of the region, however, and I believe that this branch of zoölogy would be well worth investigation for reptiles and batrachians are fairly abundant and the natives would rather assist than retard one's efforts.

The language of Fukien is a greater annoyance than in any other of the Chinese coast provinces. The Foochow dialect (which is one of the most difficult to learn) is spoken only within fifty or one hundred miles of the city. At Yen-ping Mr. Caldwell, who speaks "Foochow" perfectly, could not understand a word of the "southern mandarin" which is the language of that region, and near Futsing, where a colony of natives from Amoy have settled, the dialect is unintelligible to one who knows only "Foochow."

Travel in Fukien is an unceasing trial, for transport is entirely by coolies who carry from eighty to one hundred pounds. The men are paid by distance or weight; therefore, when coolies finally have been obtained there is the inevitable wrangling over loads so that from one to two hours are consumed before the party can start.

But the worst of it is that one can never be certain when one's entire outfit will arrive at its new destination. Some men walk much faster than others, some will delay a long time for tea, or may give out altogether if the day be hot, with the result that the last load will arrive perhaps five or six hours after the first one.

As

horses are not to be had, if one does not walk the only alternative is

to be carried in a mountain chair, which is an uncomfortable, trapeze-like

affair and only to be found along the main highways. On the whole, transport

by man-power in China is so uncertain and expensive that for a large expedition

it forms a grave obstacle to successful work, if time and funds be limited.

Back to top

On the other hand, servants are cheap and

usually good. We employed a very fair cook who received monthly seven

dollars Mexican (then about three and one-half dollars gold), and "boys"

were hired at from five to seven dollars (Mexican). As none of the servants

knew English they could be obtained at much lower wages, but English-speaking

cooks usually receive from fifteen to twenty dollars (Mexican) a month.

It was hard to leave Fukien without the blue tiger but we had hunted him unsuccessfully for five weeks and there was other and more important work awaiting us in Yün-nan. It required thirty porters to transport our baggage from the Ling-suik monastery to Daing-nei, twenty-one miles away, where two houseboats were to meet us, and by ten o'clock in the evening we were lying off Pagoda Anchorage awaiting the flood tide to take us to Foochow. We made our beds on the deck house and in the morning opened our eyes to find the boat tied to the wharf at the Custom House on the Bund, and ourselves in full view of all Foochow had it been awake at that hour.

The week of packing and repacking that followed was made easy for us by Claude Kellogg, who acted as our ministering angel. I think there must be a special Providence that watches over wandering naturalists and directs them to such men as Kellogg, for without divine aid they could never be found. When we last saw him, he stood on the stone steps of the water front waving his hat as we slipped away on the tide, to board the S.S. Haitan for Hongkong.

![]() Favorite

Fujian Sites

Favorite

Fujian Sites ![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album ![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Fujian

Guides

Fujian

Guides ![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Wuyi

Mtn

Wuyi

Mtn ![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Taimu

Mtn.

Taimu

Mtn. ![]() Roundhouses

Roundhouses

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Jiangxi

Jiangxi

![]() Guilin

Guilin

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Readers'

Letters New: Amoy

Vampires! Google

Search

Readers'

Letters New: Amoy

Vampires! Google

Search

Last Updated: May 2007

AMOY

MISSION LINKS

![]()

![]() A.M.

Main Menu

A.M.

Main Menu

![]() RCA

Miss'ry List

RCA

Miss'ry List

![]() AmoyMission-1877

AmoyMission-1877

![]() AmoyMission-1893

AmoyMission-1893

![]() Abeel,

David

Abeel,

David

![]() Beltman

Beltman

![]() Boot

Family

Boot

Family

![]() Broekema,

Ruth

Broekema,

Ruth

![]() Bruce,

Elizabeth

Bruce,

Elizabeth

![]() Burns,

Wm.

Burns,

Wm.

![]() Caldwells

Caldwells

![]() DePree

DePree

![]() Develder,

Wally

Develder,

Wally

![]() Wally's

Memoirs!

Wally's

Memoirs!

![]() Douglas,

Carstairs

Douglas,

Carstairs

![]() Doty,

Elihu

Doty,

Elihu

![]() Duryea,

Wm. Rankin

Duryea,

Wm. Rankin

![]() Esther,Joe

& Marion

Esther,Joe

& Marion

![]() Green,

Katherine

Green,

Katherine

![]() Hills,Jack

& Joann

Hills,Jack

& Joann

. ![]() Hill's

Photos.80+

Hill's

Photos.80+

..![]() Keith

H.

Keith

H.![]() Homeschool

Homeschool

![]() Hofstras

Hofstras

![]() Holkeboer,

Tena

Holkeboer,

Tena

![]() Holleman,

M.D.

Holleman,

M.D.

![]() Hope

Hospital

Hope

Hospital

![]() Johnston

Bio

Johnston

Bio

![]() Joralmans

Joralmans

![]() Karsen,

W&R

Karsen,

W&R

![]() Koeppes,

Edwin&Eliz.

Koeppes,

Edwin&Eliz.

![]() Kip,

Leonard W.

Kip,

Leonard W.

![]() Meer

Wm. Vander

Meer

Wm. Vander

![]() Morrison,

Margaret

Morrison,

Margaret

![]() Muilenbergs

Muilenbergs

![]() Neinhuis,

Jean

Neinhuis,

Jean

![]() Oltman,

M.D.

Oltman,

M.D.

![]() Ostrum,

Alvin

Ostrum,

Alvin

![]() Otte,M.D.

Otte,M.D.![]() Last

Days

Last

Days

![]() Platz,

Jessie

Platz,

Jessie

![]() Pohlman,

W. J.

Pohlman,

W. J.

![]() Poppen,

H.& D.

Poppen,

H.& D.

![]() Rapalje,

Daniel

Rapalje,

Daniel

![]() Renskers

Renskers

![]() Talmage,

J.V.N.

Talmage,

J.V.N.

![]() Talman,

Dr.